The Epic Narrative as Multiplicity: In Conversation with Ashish Sahoo

The Epic Narrative as Multiplicity: In Conversation with Ashish Sahoo

MALAVIKA MADGULKAR

12 July 2021

Ashish Sahoo, the 2018 grantee of the Umrao Singh Sher-Gil Grant for Photography is a sculptor, filmmaker and photographer with an MFA from the College of Art, New Delhi. Exclusively employing analogue methods in his photographic practice, Sahoo emphasizes interactivity and viewer participation in his work.

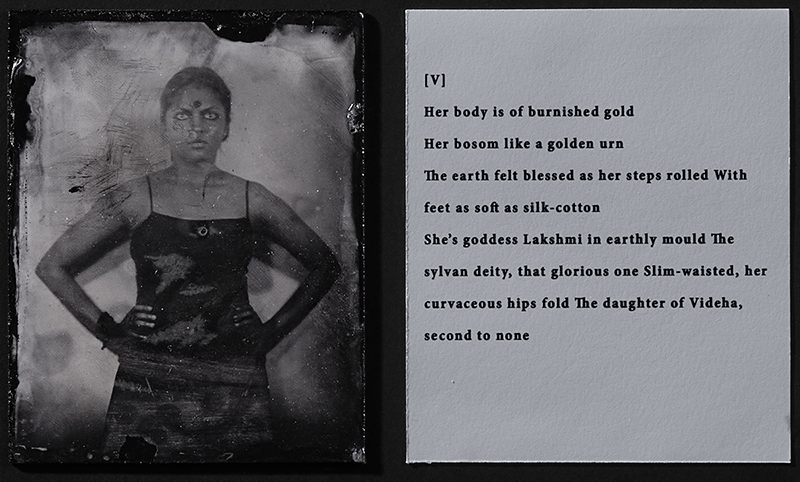

His project Narrative-Flux is a contemporary retelling of the Ramayana presented through a series of ambrotypes or wet collodion process plates arranged alongside lines of poetic text in an interchangeable sequence. For this project, Sahoo has worked with stage artists including Chhau dancers and theatre actors, bringing the dynamism of their performances to the still image. Narrative-Flux puts across a nuanced and fluid engagement with the epic that breaks with dominant representations of Rama, Lakshmana, Sita and Ravana and makes space for alternate readings. This is a project interested in exploring how even the oldest stories exist in a state of constant transformation as their interpretations are influenced by the socio-cultural environments within which they are placed, their transformation from orality to written texts at different points in history, and the personal narratives of those who engage with them.

In this conversation with Malavika Madgulkar, Ashish Sahoo elaborates on the trajectory of the project’s development and his motivations behind encouraging reworkings of an epic that has deep political significance in the country.

MM: Your project works with epic narratives that have immense socio-political resonance. How did you come to the concept for Narrative-Flux?

AS: The idea for Narrative-Flux planted itself in my mind 7 years ago. The political scenario of religious conflict has always been present, but I didn’t see much of it growing up. I was born in Cuttack in Odisha where I had friends who are Muslims, Christians and Hindus. They used to visit my family and we would all eat together. For my Bachelor’s degree, I moved to Santiniketan where religion wasn’t really discussed at all, people talked instead about Tagore and Nandalal Bose. That was until I came to Delhi, where caste and religion were – and continue to be – very much in the foreground. While I was coming to terms with this, the new government came in and with that came a wave of violence in the name of religion, specifically in the name of Rama. Growing up in a Hindu family, I was aware of this context, and the Ramayana was a part of my childhood reading. As all of those memories came back to me, I had a lot of questions – it seemed to me that in Odisha we were telling a different Ramayana. The stories of Ramayana that I had heard from my mother and grandmother were different from the stories that were told in Delhi. This led me to question how a text that has multiple contradictory interpretations can come to be regarded as a single narrative.

Around that time, I came across Three Hundred Ramayanas by A.K Ramanujan and Ramanujan’s argument about there being a multitude of Ramayanas in existence opened my mind up completely. I started researching various Ramayanas – the Thai Ramayana, the Burmese Ramayana, the Sri Lankan Ramayana. I found that there are so many versions even in India – the Buddhist Ramayana, the Jain Ramayana. There are 25 different versions in Sanskrit alone. My research showed me that texts are selectively chosen, that they can be manipulated in order to create a dominant ethos for a particular culture. This led me to the concept for Narrative-Flux where I decided to work with four prominent characters from the Ramayana – Rama, Lakshmana, Sita and Ravana.

MM: How did you go about incorporating poetry/text in your project? I understand you collaborated with the writer Sourabh Harihar to adapt translations of two versions of the Ramayana to your project. Could you outline that process for us?

AS: The final images that I worked on for the Umrao Singh Sher-Gil Grant are arranged in a certain way – if you read the text that accompanies one of the images from Narrative-Flux, it will tell you what is happening in that particular image. At the same time, the bits of text have been composed in such a way that you can switch around the images next to them. The moment you change the image next to a section of text, the characters in that image take on the meaning of the text. The fragments of text that I’ve selected don’t correspond to any singular character role in the Ramayana.

That was the idea of the project – to play around with the subjects in the photographs and the accompanying text so that the roles and qualities generally ascribed to these characters could be interchanged. That was the idea that kept coming up when I was researching the Ramayana. In the dominant version of Ramayana, for example, we understand Rama as the embodiment of duty and morality but in some Ramayanas, Ravana is the character who leans more towards moral good. The images and text in my project tell a certain story, but that same story holds the potential to completely change the minute you swap an image or one text for another. That was the reason I called the project ‘Narrative-Flux’. Right now, the text is coordinated with the images in a particular way but I do not see that as a fixed sequence.

Working with Sourabh was a really interesting experience for me. He has previously worked with the Mahabharata – told from Draupadi’s point of view – and based a performance on it. So when I went to him with my idea, he was really excited about it. It was important to me that the text we produce be playful – where the recognizable events within the narrative would be left intact but at the same time the characters would be open for alternate interpretations.

We worked on this for 6 or 7 months and produced several drafts together. It was fascinating for me to see how he worked because he is both a writer and a theatre director. My project had a lot of performative and theatrical aspects and I was also being guided by Anuradha Kapur. So it all came together in a very beautiful way. We are also planning to build more text around this project in the future.

© Ashish Sahoo, ‘Narratives-Flux’ /Umrao Singh Sher-Gil Grant for Photography [2018], SSAF.

MM: You mentioned how different variations/readings of the Ramayana can interchange the roles of the moral protagonist and evil villain by casting Ravana, instead of Rama, as the heroic figure. I’m wondering about the other two characters – Sita and Lakshmana – and how they factor in. Could there be a narrative of the Ramayana that allows for Sita, for example, to take the place of Rama?

AS: Yes, of course, I see all of the roles as interchangeable. My project is not just about mythology or the Ramayana, but also looks at how certain beliefs have emerged as dominant discourses at different points in history. There are questionable moments in the stories of these characters that our political surroundings discourage us from asking. But the entire idea of the project was to raise those questions. Regarding whether Sita can replace Rama, I believe she can. In the Adhbhuta Ramayana as well as in the Tamil story of Satakantharavana, Sita fights Ravana and makes herself free.

I want to question what we mean when we say ‘good’ or ‘evil’. Ravana is known as a Rakshasa but this term originates from a word meaning ‘protector of forests’ – a reference to tribal people. Those in power at the time – the kings, the princes and Brahmans – were taking away the land of tribal people who were resisting them. They have been portrayed as demons – with multiple heads, and hands and feet. But if you remove these fantastical aspects of the mythology of gods and demons, you can see very clearly how these injustices continue today, with indigenous people fighting against the takeover of their land being framed as the enemy. The ‘good’ characters, the ‘bad’ characters . . . these roles have always been slippery.

If we swap around the photographs and texts from Narrative-Flux and put Rama in place of Ravana as Sita’s abductor, such a reading is certainly possible. In dominant tellings of Ramayana, Sita requests Rama to allow her to join him in the forest, but in the Jain Ramayana, Rama forcefully drags her along. In the Santhal Ramayana, Sita develops romantic feelings towards Lakshmana and Ravana. We have a sexist and misogynistic Ramayana, but we don’t have to keep ourselves closed to alternative readings.

MM: The lines of poetry presented alongside the images reference specific episodes and events in the Ramayana. How did you choose which episodes to include?

AS: As I was doing the research for my project, I decided to focus on one specific kand from the Ramayana – the Aranya Kand. This is where Rama, Lakshmana and Sita arrive in the forest and Sita is abducted. This is the part I found most interesting because in the many Ramayanas I researched, this was the moment where the storylines differed the most. The reasons behind why Ravana abducts Sita, why Sita comes to the forest but Lakshmana’s wife does not . . . I saw a lot of politics in that particular part of the Ramayana.

MM: Your project involved working closely with stage performers as your subjects. What was that process like? Do you see Narratives-Flux as a collaboration between the artistic practices of dance, theatre and photography?

AS: I understood my project as a collaboration between me and the performers from the very beginning. Before my first shoot with theatre actors, I held auditions. Once the character was chosen, we’d chat together, we’d start discussing. These are theatre actors who have performed for many years so I needed their input; I’m not a director and this was something we had to do together. Before every shoot we rehearsed the entire scene like a theatre performance. Photography works with the still image but I work with people who are live actors. If I had told them to give me a certain expression, they would’ve done so, but it wouldn’t have worked as a still image. So they would perform for 10–15 minutes and then I would tell them, “Lets perform again”. Then at the moment I wanted to shoot, I would say, “Stop here, just be here, I’ll shoot”.

Ashish working with an actor at the pre-shoot rehearsal for Narrative-Flux.

Ashish during the production of Narrative-Flux.

MM: Your photographic practice involves using techniques from history that have now become obsolete. Could you tell us about your decision to use ambrotype processes for this project?

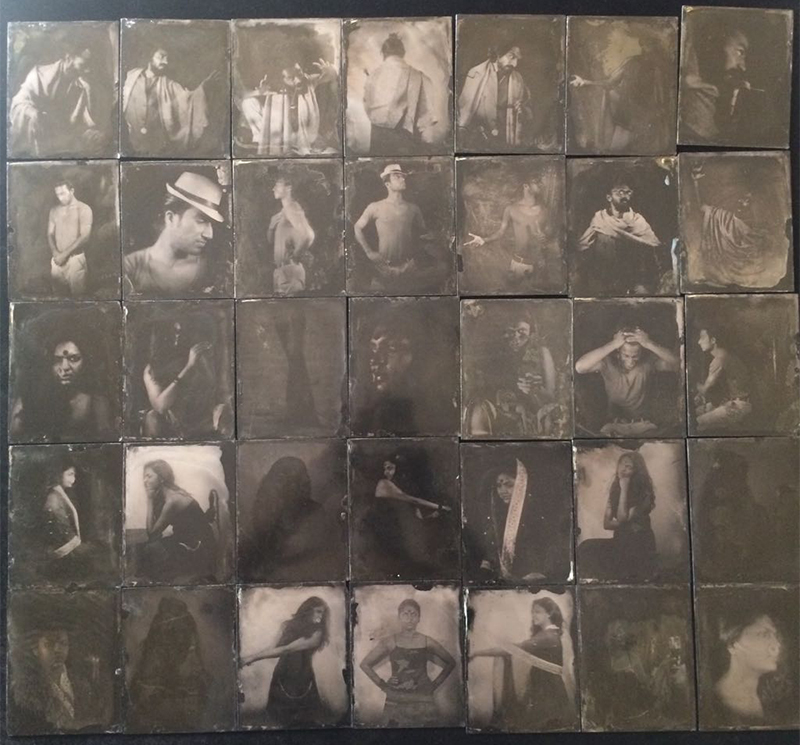

AS: I work mostly with alternative processes and I shoot only analogue because I don’t have a digital camera [laughs]. For this project I used a 19th century technique called the wet plate collodion process. This entails shooting the image on a glass plate. Before starting this project, whenever I worked with wet plates, or handed one over to someone to hold and view the image, they were afraid of how fragile it was, of dropping it or breaking it. Fear was an emotion that I had to deal with too as I was worked on this, because of the political sensitivity of this project and its ability to provoke a lot of rage and put me in danger. This fragility of the topic I was dealing with connected with fragility of the material – glass – that I was working on.

Ambrotypes from Sahoo’s work in his studio.

MM: How has Narratives-Flux changed and developed over the time you have been working on it? You mentioned that you were working with Chhau dancers to begin with and then you started working with theatre actors. What has the trajectory been like for you?

AS: I remember seeing Chhau dancers at festivals growing up in Odisha. Chhau dance is particularly interesting because you completely take on the identity of the character that you play. Before the grant, I went to Purulia in West Bengal and stayed with a Chhau dance group in a village. From there, I went to Mayurbhanj in Odisha which is also famous for Chhau, and I was with a group there for 6 or 7 months. When I told them about my idea and what I was thinking of with the Ramayana, that group of dancers told me that it was against their beliefs. When I came back to Delhi after finishing my research, ready to start shooting, I realized that I couldn’t do it. I was close to the Chhau dancers and I understood the philosophy behind their art. So I decided to not photograph real Chhau dancers out of respect for their work. My conscience wouldn’t allow me to do.

Because I am a sculptor and have studied sculpture, I started making my own masks. I made masks for Rama, Lakshmana, Sita and Ravana. Chhau costumes are huge and I didn’t have a large space to shoot (I was shooting everything inside my studio), I decided to use more contemporary costumes. At that point I found contemporary dancers who were practicing Chhau dance in Delhi. Because in Delhi you can practice whichever dance you want – no one will ask you whether you are religious or not – they were very open and said that they will perform for me. That is how I came to Chhau dance. The thing is that theatre made the project more solid; in the end, these stories are themselves theatrical. When I decided to work with theatre actors and to see how that goes, I realized that that was what I was looking for.

Photograph produced for Narrative-Flux in the initial stage of the project.

Ashish photographing a dancer in his studio.

MM: You have mentioned that your photography practice seeks to encourage viewers to participate in and engage with it. How do you envision viewers interacting with Narrative-Flux?

AS: In order to let the viewers engage more with the project, my plan is to make a physical game platform of sorts. The text will be broken up into words and the viewer will be able to interact with these text fragments and the image plates to create variations of the Ramayana. Like with any game, there will be certain rules and regulations – there will be a designated space to put a word down and once you put it down you won’t be able to take it back. Once you put down, say, ten words and create a sentence, you will have to put these sentences together with images to produce a story. Every time a new person interacts with the work, new narratives will emerge.

MM: Do you have any other projects in the works at the moment?

AS: A project that I have been working on since last year, called BLINK, just launched at the beginning of July. It is an interactive gaming project developed in collaboration with the Iranian visual artist Zahra Yazdani. The motivation behind it was to point to the idea that ‘truth’ cannot be regarded as unified or consistent. Truth and reality are ever-changing narratives passed from one to another and our current communication technologies – the way that information travels through social media – make that visible. The online game is our way to address this idea through generative and playful interactions.

Recently I have also been working on two books which I’m planning to publish. One is a collaboration with poets from Kashmir and the other is my first time working on myself as a subject.

All images have been reproduced with the permission of the author.