Thawing Temporalities: In Conversation with Prajakta Potnis

Thawing Temporalities: In Conversation with Prajakta Potnis

MALAVIKA MADGULKAR

04 July 2022

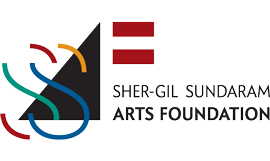

2017 Umrao Singh Sher-Gil Grant for Photography grantee Prajakta Potnis’ When the Wind Blows appropriates the space of a frost-lined outdated freezer cupboard in a domestic refrigerator as an ethereal yet foreboding environment for her photographs. The making of these images involved placing non-descript objects in an elaborate staging process within the unusual studio space of this freezer. Her project thus investigates the passage and experience of time and the ‘freezing’ of a moment through the technologies of both photography and refrigeration.

The icy landscapes of Where the Wind Blows, entirely devoid of human presence save for a few found scrap objects, evoke the quiet horrors of post-apocalyptic landscapes, frozen deserts and climate catastrophe. With allusions to the precarious presents and futures on Earth, Prajakta asks pressing questions of the Anthropocene, climate destruction and the legacy of the human. In this conversation, she tells us more about temporal movement and stillness, about how the domestic is always already linked to the militant and the sovereign, and how object-oriented philosophy has influenced her practice.

MM: Could you tell us about the title of your project and how you came to choose it?

PP: The title was adopted from Raymond Brigg’s 1982 comic book titled When the Wind Blows which was later made into an animated disaster. Both the film and comic book are suggestive of a moment in reckoning, building on the anxiety of the Cold War. The story is an account of a rural English couple’s attempt to survive a nearby nuclear attack and maintain a sense of normalcy in the subsequent fallout and nuclear winter. Having survived the Second World War, the couple is optimistic and hopeful of overcoming this disaster. It is heart-wrenching to see them worry about their everyday rituals like making tea as their bodies wither due to the exposure. There is this particular moment where, after hearing a warning on the radio of an imminent strike, they are advised to take immediate shelter. The wife, while being dragged out of the kitchen as she tries to finish her chores, screams that she has left the “oven on” and that “the cake will be burnt”! The animation depicts the nuclear strike in slow motion, with a haunting track that has her saying “The cake will be burnt”. This locution keeps echoing in the background as the camera pans over the city that slowly dissipates. The voice-over pertaining to a minor domestic set-back against images of mass destruction is absurd yet it situates an individual within a larger narrative. Within my practice it has been important to assert the voice of an individual, to reflect on how top-down policies affect us in our private lives. Most of the works were conceived post my residency at the Kunstlerhaus Bethanien, Berlin in 2014 that threw up the “kitchen debate” anecdote at the peak of the Cold War and related anxiety. It’s not like the veil or cloud was totally off. As the situation spiralled in Ukraine in 2014 , Berlin had this quiet sense of dread in the air with other urgent issues lurking, especially the ecological crisis. I wanted the title of the project to have some connotation to an uncertain atmosphere, for it to relate to the weather, like a forewarning of an approaching storm. It was the unassuming and non-threatening title of the comic book with a dreadful plot that stayed with me. At some point as the works progressed, I was certain of quoting it.

© Prajakta Potnis, ‘When the Wind Blows’/Umrao Singh Sher-Gil Grant for Photography [2017], SSAF.

MM: There is a clear resonance between your medium – photography, and your setting, the freezer; it could be said that both perform the function of slowing down or ‘stopping’ time. What drew you to explore this process of halting and capturing a fleeting moment?

PP: I am interested in the stillness of an image; through the medium of painting or photography my endeavor has been to pause and examine the way time functions within an image. Time is arrested in such different ways within a two-dimensional painted image and a photographic image. According to John Berger, “A drawing contains the time of its own making, and this means that it possesses its own time, independent of the living time of what it portrays”. Still-life paintings may seem unassuming at first glance but it is surprising to see how an arranged set of mundane objects manage to hold the attention of a viewer and draw the viewer within. It could be the way various surfaces are rendered, thus embedding the making time within the image. One may choose to spend more time painting a particular detail while contributing much less time to render a backdrop or a drapery, thus making it possible for a painting to have multiple quantities of time squeezed within.

Does this mean then, that there is some kind of a uniform time within a photograph as compared to a drawing or a painting? In a photograph, a shot confronts us with a tiny fragment of time frozen and stopped forever as if it had been mummified, this contraction and expansion of time within an image is something that intrigues me. The process of staging installations within a freezer is lengthy and meticulous, and photographing them marks time differently. Here, the process of building and constructing seems to add individually to the final frozen image.

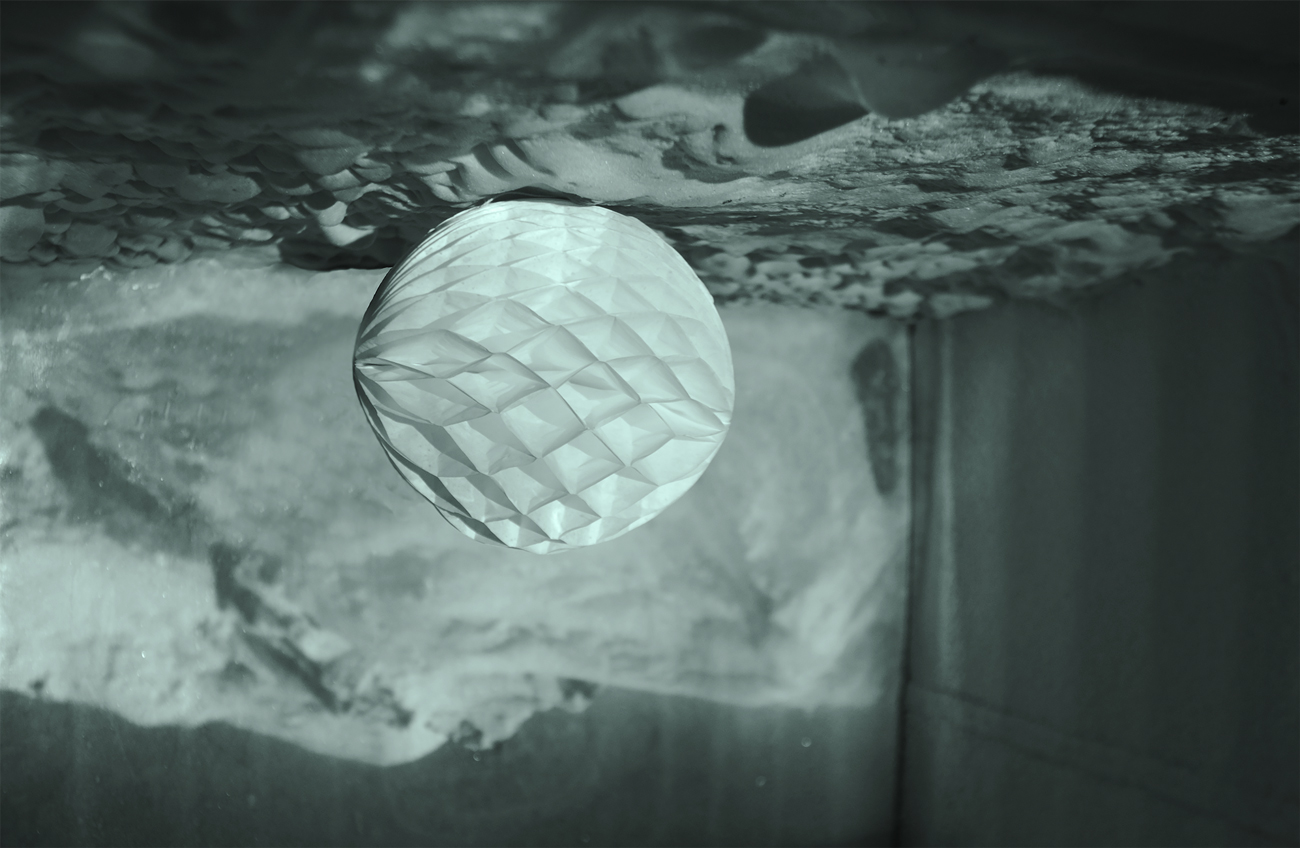

The freezer for me becomes a conceptual space to stage a dialogue of some kind on a frozen decay. Is it possible then, to actually sculpt or carve a physiological scape? In Berlin, I came upon a bunch of film slides from the ‘70s, these were mainly photos of various places visited by a tourist. Watching the film slides through a slide projector in my studio took me back in time, it was like watching a travelogue of a person I hadn’t known or met. By projecting these found landscapes onto the walls of the freezer, I tried to open up one or more of the walls to create a space within a space, and in some instances carve a window within this enclosed environment quite similar to the wallpapers of snowclad mountains found in the living rooms of middle-class homes, especially in the early 1990s. These are images of elsewhere, these unattainable landscapes in time which could only be reimagined through memory and which are now preserved in a state of pause.

The film slides, which the artist came across in Europe, being projected in the artist’s studio.

MM: Your photographs transform an everyday element in the domestic space – the refrigerator – into an environment that appears otherworldly, deserted and, as you once put it, ‘like the set of a sci-fi film’. What was your motivation behind making this seemingly apocalyptic landscape visible within the ordinary setting of the household kitchen?

PP: At the peak of the Indian summer, as a kid scraping frost and eating it as a makeshift popsicle from a freezer, having not seen or experienced snow, the inside of the freezer was a space of wonder – it was the only space where one could imagine what a snow-clad landscape looked like. I have always been fascinated by the interiors of home appliances, from the inside of microwaves to refrigerators. The interior cavity of a home appliance has always felt so strange and distant at the same time, as though it had no connection with its surrounding, like the steel clad walls of a washing machine or a microwave. It was quite by accident that a British military scientist invented microwave technology while trying to devise a death ray to blow up enemy planes. The modern kitchen and war are connected, intertwined. During the Cold War, many exhibitions involving kitchens were set up as East–West cultural exchange arenas and served as rhetorical and symbolic battlegrounds. Richard Nixon and Nikita Khrushchev’s famous “kitchen debate” in 1959 involved more than the virtues of American appliances. Both Nixon and Khrushchev recognized the political symbolism of the modern kitchen; the kind of technological innovation represented in this everyday context spoke to the political system that produced it. The kitchen connects the “big” politics of politicians and statesmen to the “small” politics of users and interest groups. Research on materials allowed the use of different types of polymers, unlocking infinite shape possibilities. New technical perspectives combined with an interest in abstract futuristic shapes lead to what is known as Space Age design. It is interesting how space exploration has influenced product design. The temperature-controlled environment within a refrigerator with its ethereal light bears resemblance to an abandoned film set. As thick layers of frost deposit within the freezer of an outmoded refrigerator – a phenomenon less visible in the modern frost-free refrigerators – simulating snow clad deserted landscape or a terrain of an unknown planet with melting glaciers, the freezer seemed like an appropriate space to establish the dialogue around the Anthropocene through the realm of the domestic – the private.

A customised freezer, based on the artist’s design, being assembled at a workshop in Goregaon West.

MM: Many of your photos show single objects suspended alone in this unearthly, frigid environment. These objects — polystyrene packing materials, a paperweight, a plastic bag — are ones that would otherwise be overlooked, forgotten or discarded. What was your intention behind centering these objects in your work? How did you choose them?

PP: The process of zeroing down on an object is random-like and at the same time decisive. It seems to be driven by an instinct based either on my memory of the object or the moment in which I encounter it in its surrounding. Over a period of time, I have realized that there is some kind of a pattern to this random intuitive selection. I am drawn towards a specific kind of things or materials; these could be by-products or smaller components of a larger machine, like blades from a mixer-grinder or discards from packaging materials. By detaching these parts from their original apparatus and observing them in isolation as individual objects, they seem to state their own identity. Timothy Morton in The Ecological Thought employed the term ‘hyperobjects’ to describe objects that are so massively distributed in time and space as to transcend spatiotemporal specificity. A hyperobject could be as vast as black hole, or global warming. It could be the sum total of all the nuclear materials on Earth, or just the plutonium, or the uranium. A hyperobject could be the very long-lasting product of direct human manufacture, such as Styrofoam or plastic bags. Morton describes the origin of hyper¬objects as oracular – like a radio transmission sent from the future. I may be accidentally choosing objects which may relate to the principle character of a hyperobject. It is not just the objects that I choose and stage, the site of the freezer might also fall in a similar category.

The process of staging is quite similar to the way a still-life is arranged, from the light falling on the objects to the textures that are created. The scale of these objects is completely altered while photographing, size becomes relative, and hence, they can become gigantic compared to their original size. Also the space of the freezer, its sterile character, helps to simulate a room; it is the camera and its lens that manages to construct a deceptive composite view.

© Prajakta Potnis, ‘When the Wind Blows’/Umrao Singh Sher-Gil Grant for Photography [2017], SSAF.

MM: In your artist statement you make a reference to the seed vault in Svalbard — a storage facility built into a permafrost mountain where seeds are stored in case of global crop failure or climate catastrophe — as an impetus in your exploration of the freezer space. Could you tell us more about how you understand the seed vault in relation to your work?

PP: When I came across images of the Svalbard Global seed vault which is located on a Norwegian island in the remote Svalbard archipelago, I was simply astonished by its architecture and its location. An impenetrable vault that provides security to the world’s food supply against the loss of seeds in gene banks due to any unforeseen reason, from equipment failures, funding cuts, war, sabotage, disease to natural disasters, was simply stupefying. Although recently the impenetrable seed vault turned out to be not entirely failproof (there was news of it being flooded which raised security concerns), the site had got me curious for being an archetype for doomsday architecture. The space has allusions to an apocalyptic future, for it is one of largest deep freezers that store seeds in sub-zero conditions. The interior space of the seed vault with its temperature controlled environment, allied with my interest of the idea of sterility and space within the domestic freezer. In [an early image titled] Capsule 5, by placing an egg on the frosted surface, I meant to provoke the idea of egg freezing, of leaving a probable life in a state of pause.

© Prajakta Potnis, Capsule 5, Submitted as part of the artist’s application to the Umrao Singh Sher-Gil Grant for Photography [2017].

All images have been reproduced with permission of the author.