05. the battle of beginnings

05. the battle of beginnings

To bury the dead is but one part of a procedural endeavour. A single step into the corridor that separates here from hereafter.

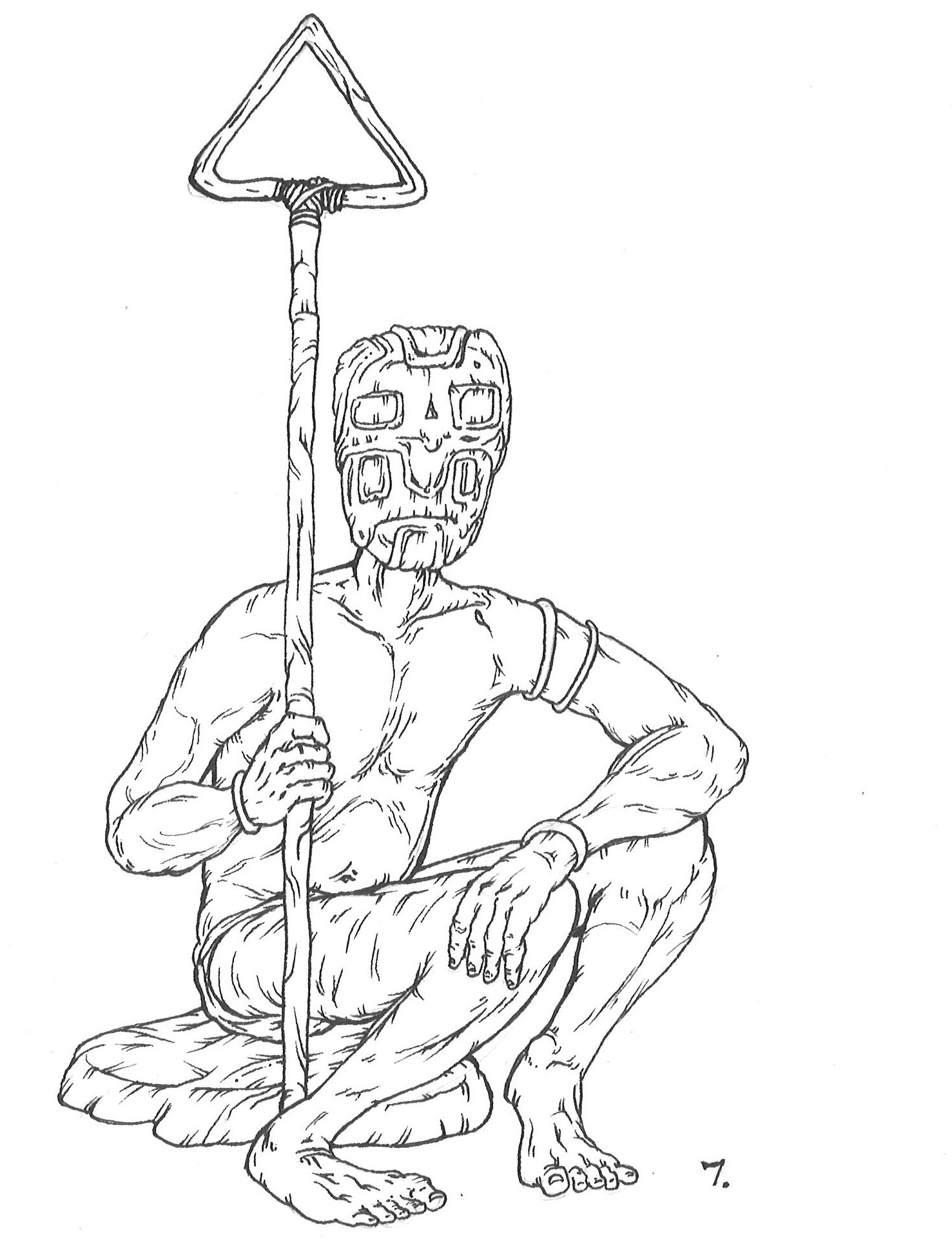

In ferrying itself across this corridor, humankind has manifested empires, rebellions, technology, theft, theatre, political campaigns, plagues, inoculation, indoctrination, belief systems and heresy. This mosaic of methods, when held together, measure the gross weight of human civilization.

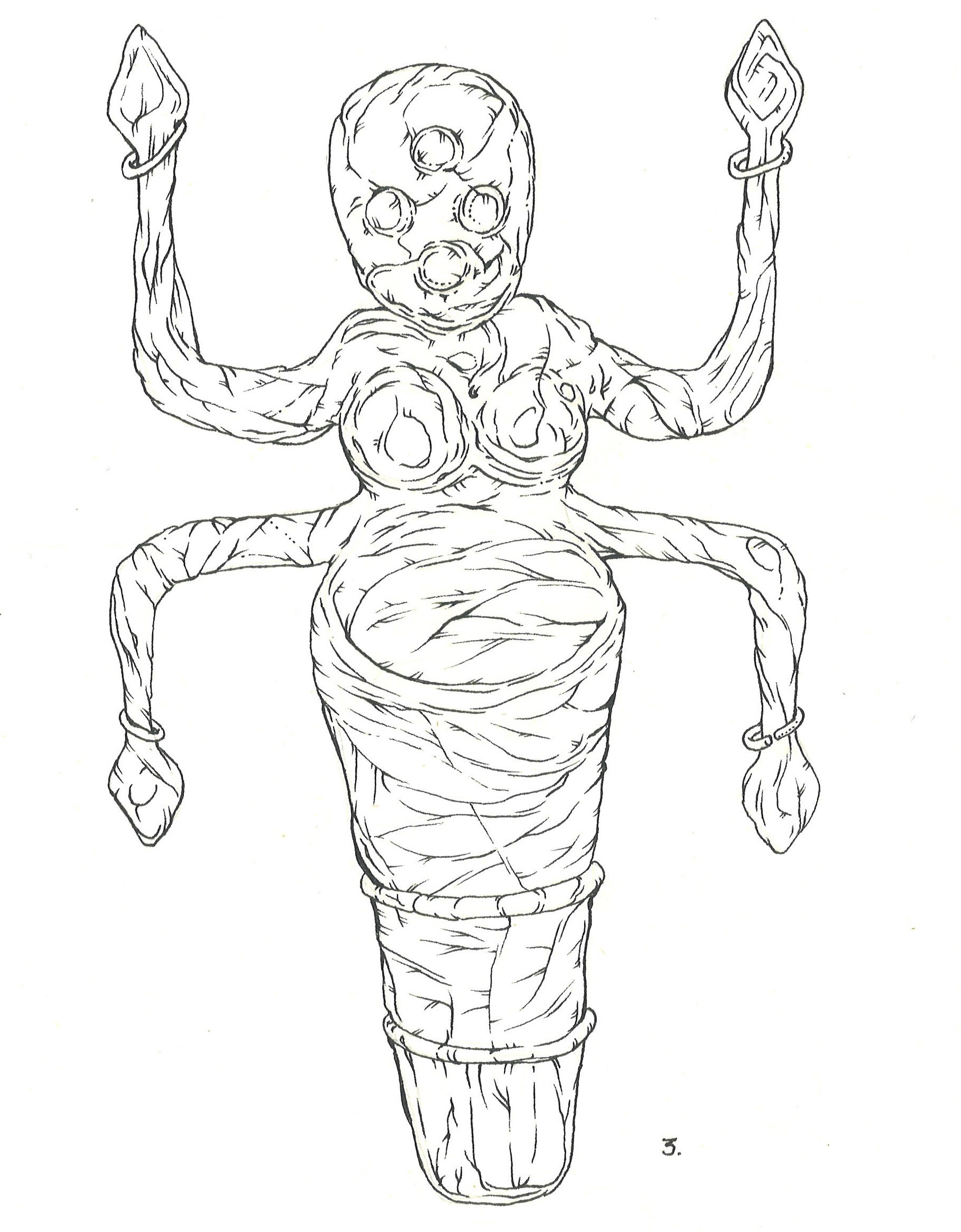

The origins of this weight are entombed within a mythological doublet of two opposing tales. The first, attributed to Rousseau, imagines the origins of humankind as a fall from grace.

It supposes we began as small bands of brotherhood. We thrived within never more than miniscule groupings of ten or twenty people in this Edenic utopia.

However, with the arrival of civilizational complexity, and their ensuing elaborations – in the forms of sect, structure, state and society –we lost touch with our innate selves, our brotherly nature bludgeoned out by bureaucracy.

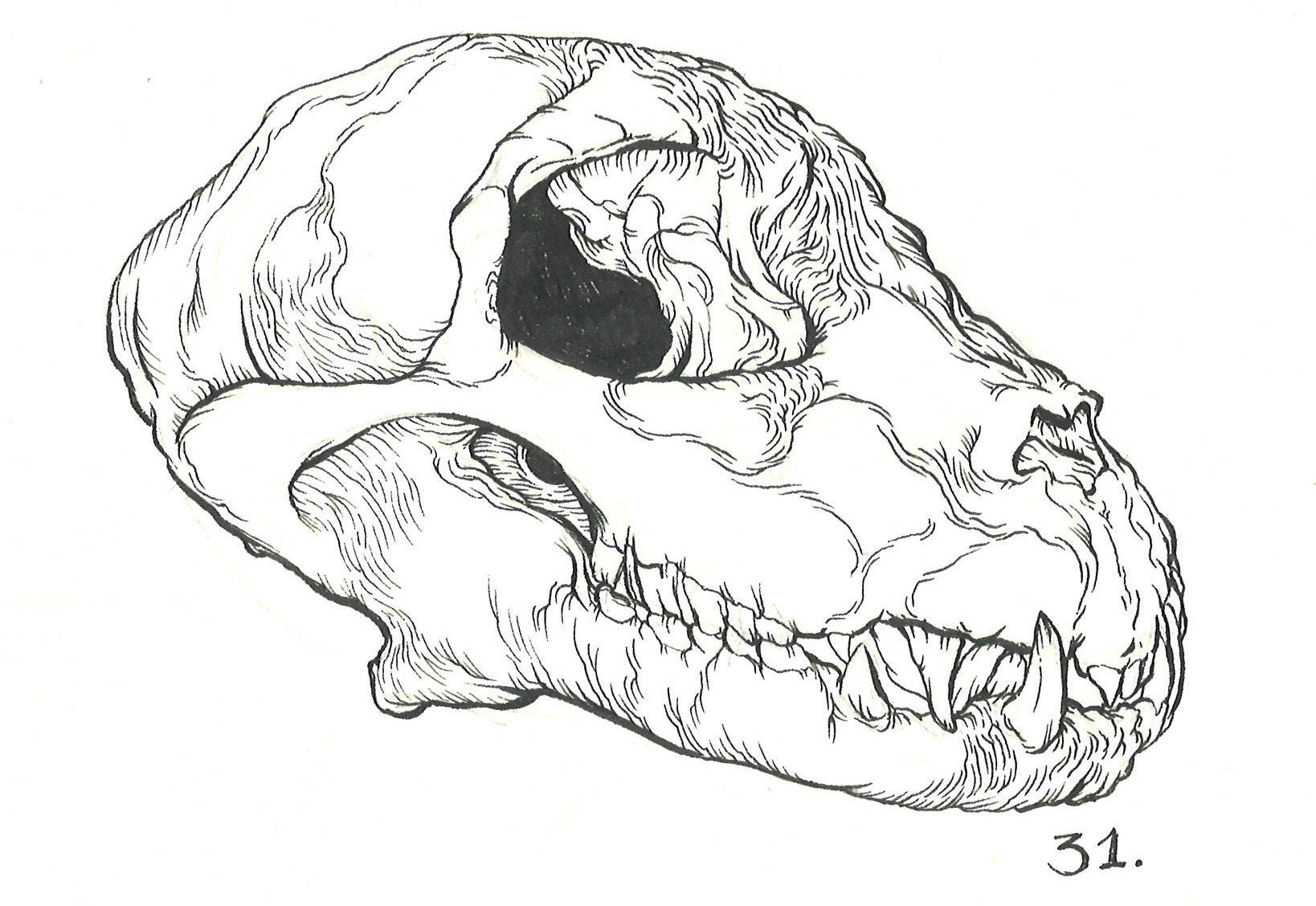

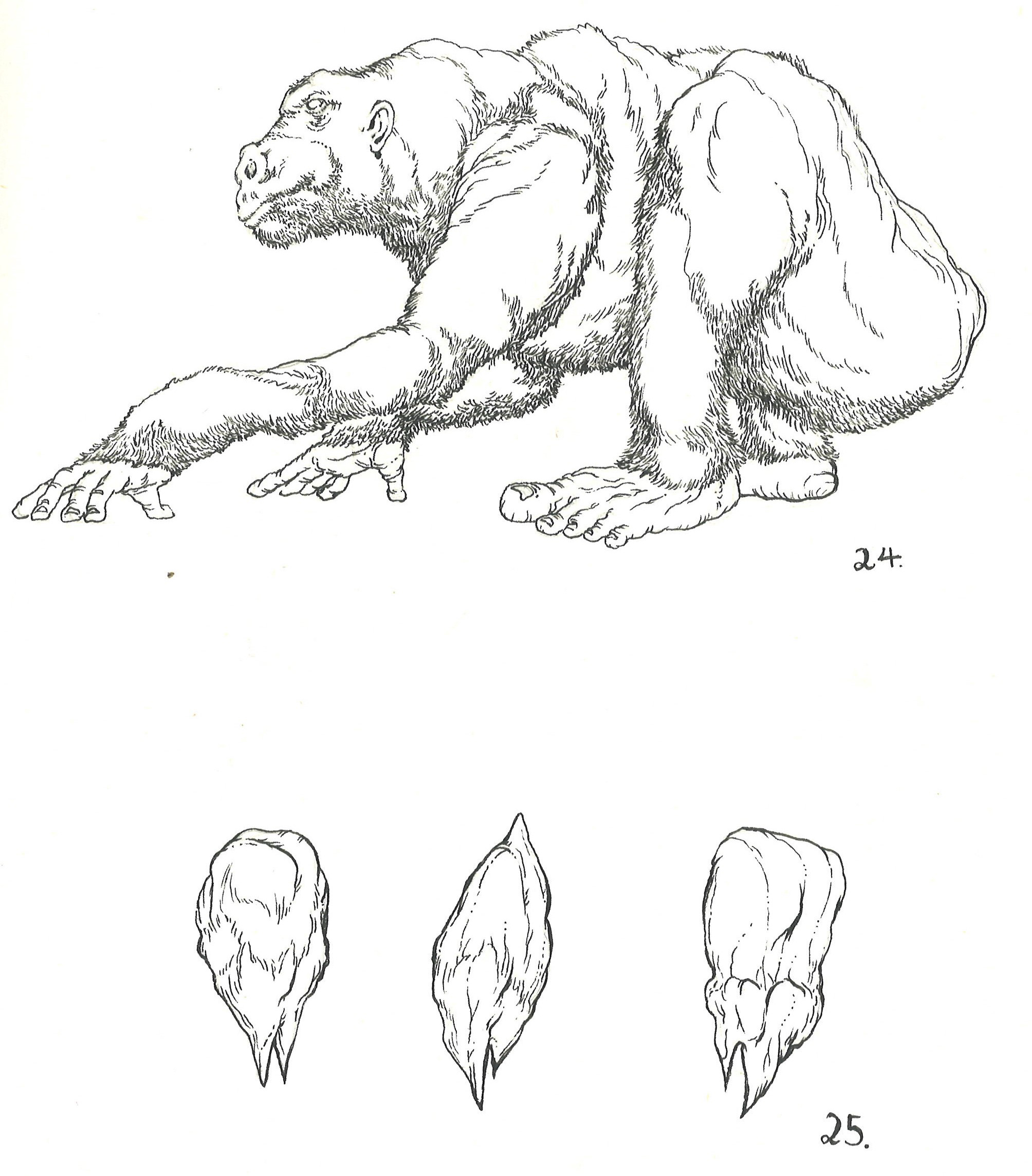

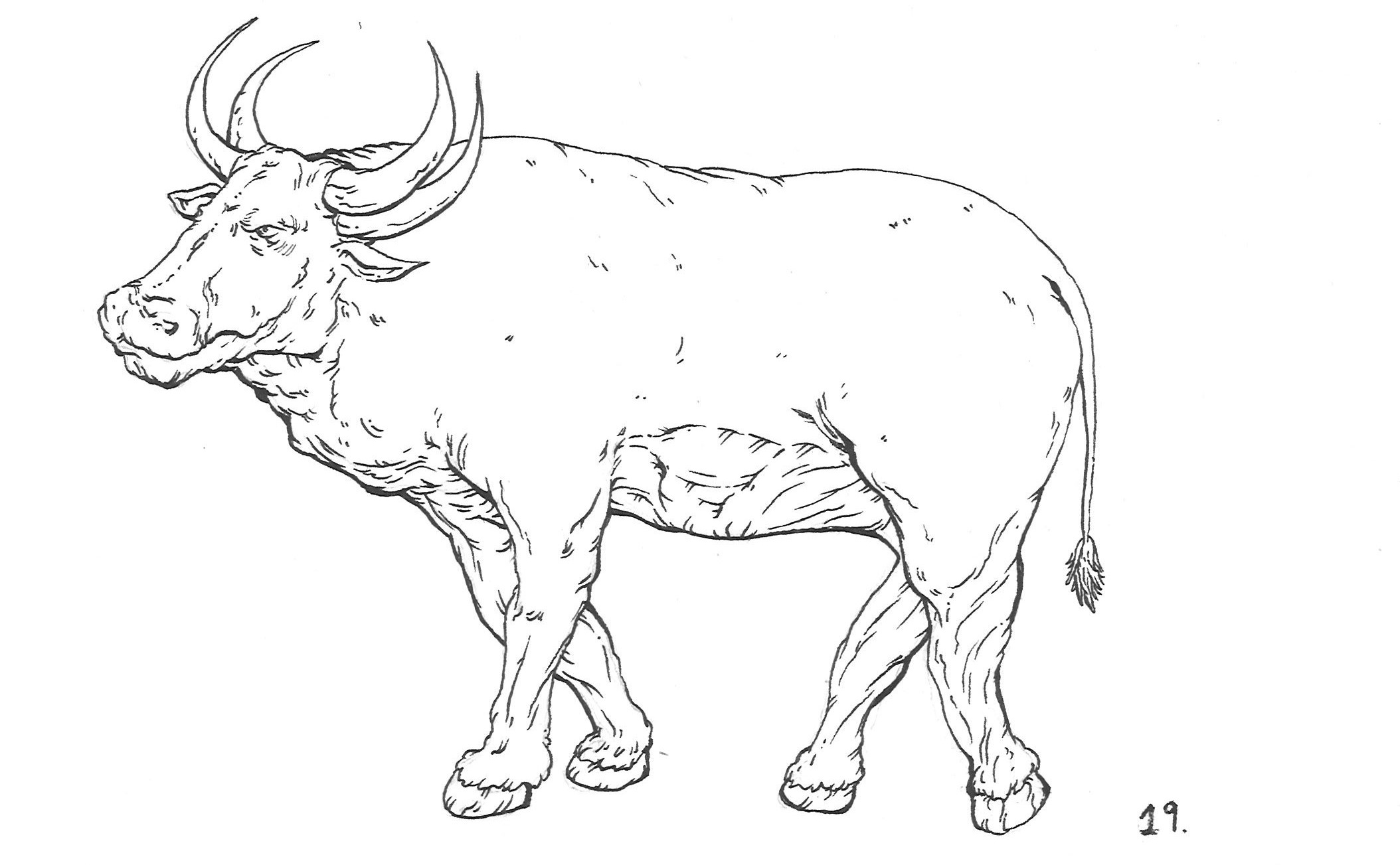

The second myth, attributed to the Leviathan of Thomas Hobbes, purports humanity as innately barbaric.

Humans, it tells us, are a self-serving lot, forever driven to accumulation. We are nomadic, brutish, boorish and ferociously feudal beings, waging perpetual war upon ourselves.

Insofar as there has been any alleviation from this blighted state of being, it argues, it has been entirely due to the establishment of the very systems of civility that Rousseau’s myth complains about. For what was required for civilization to begin was a good push against our innate animalistic instincts.

Caught within this dialectical wrestling match of our opposing origins, we find ourselves at an epistemological impasse, one as old as time itself.

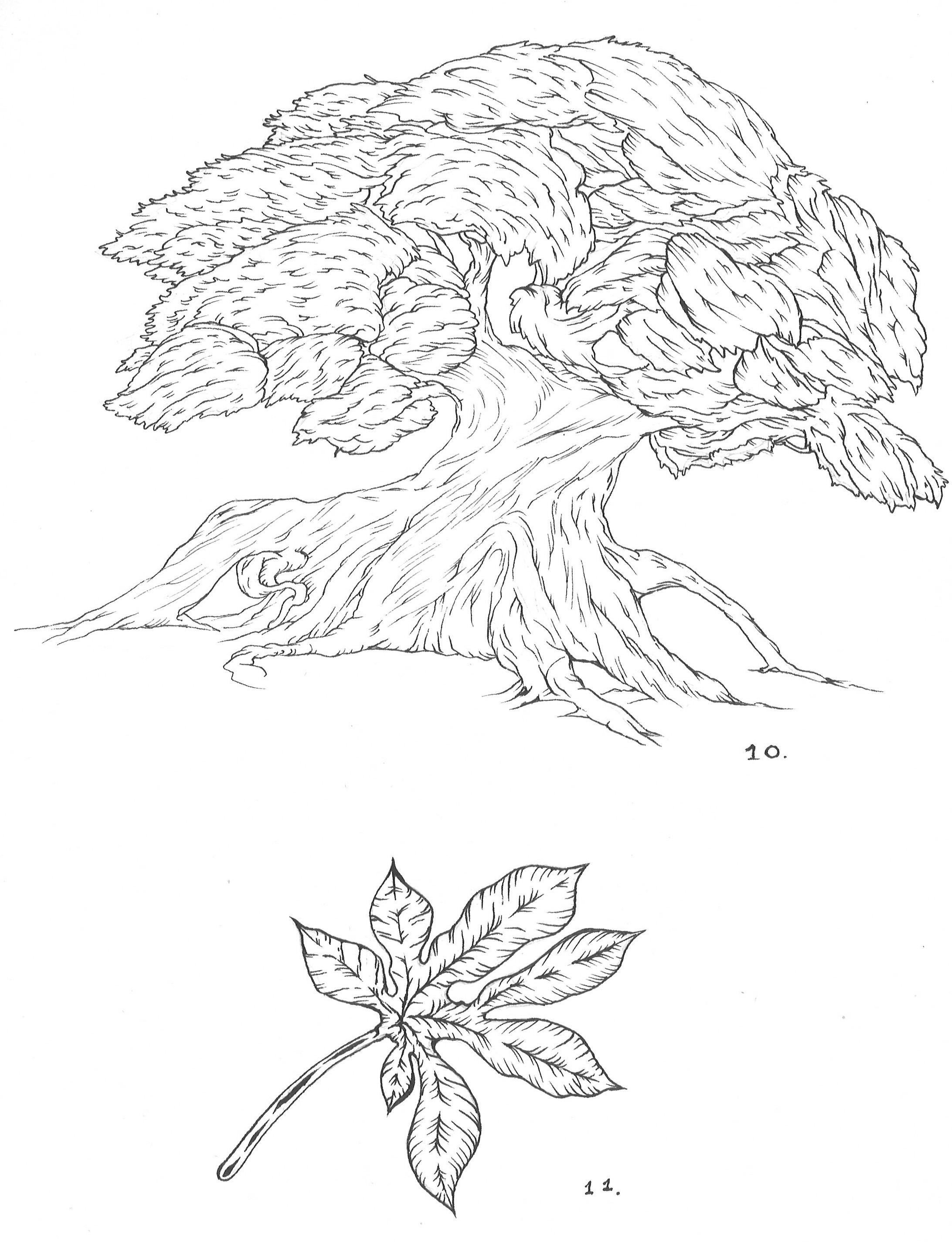

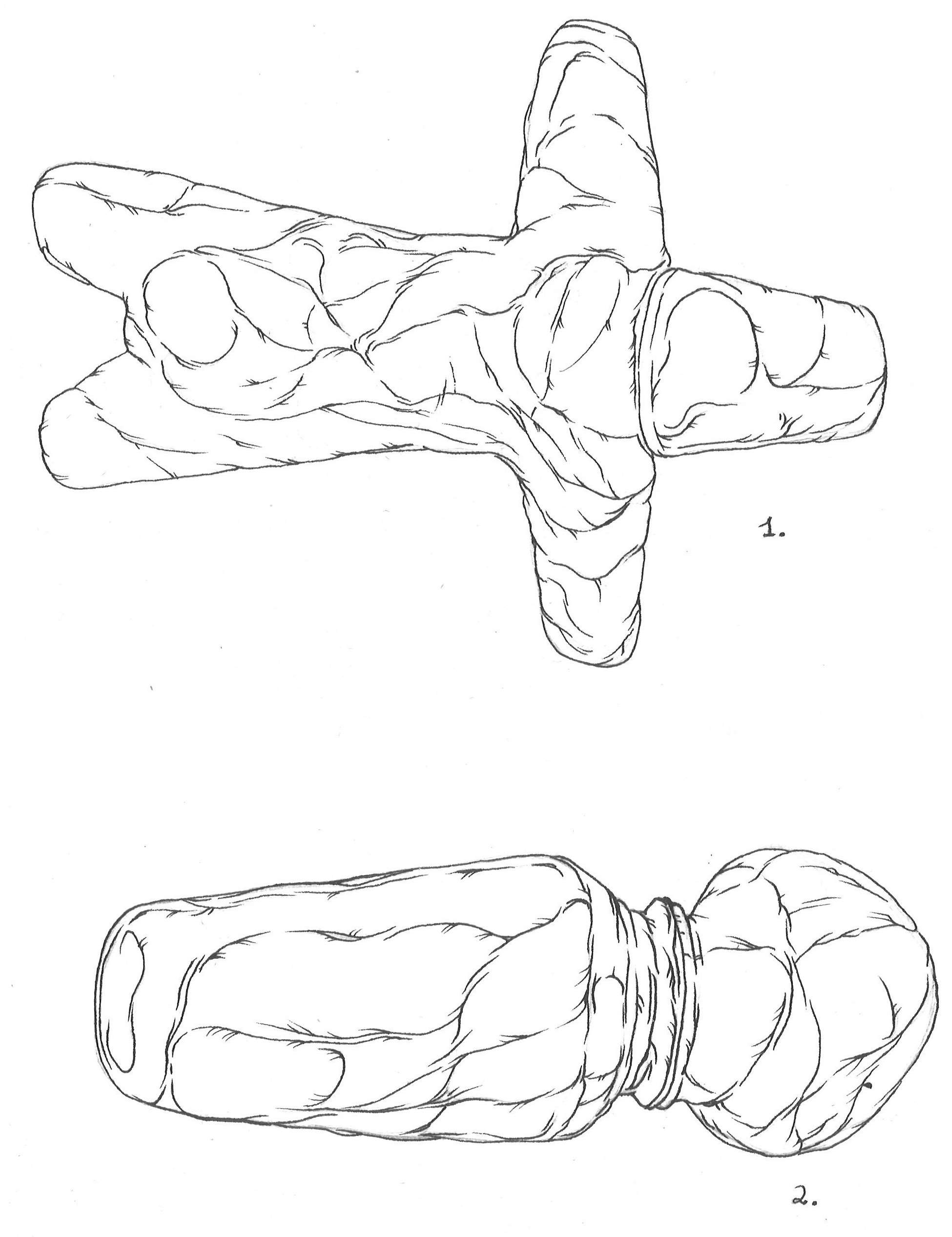

Yet both claimants to our beginnings are merely contorted fabulations, imposing themselves upon an adamantly occluded past. Fragments of clay pots, bowls, blades, grindstones, wharfs, cenotaphs and all that emerges from the soils of time, finds itself conscripted to this ancient battle.

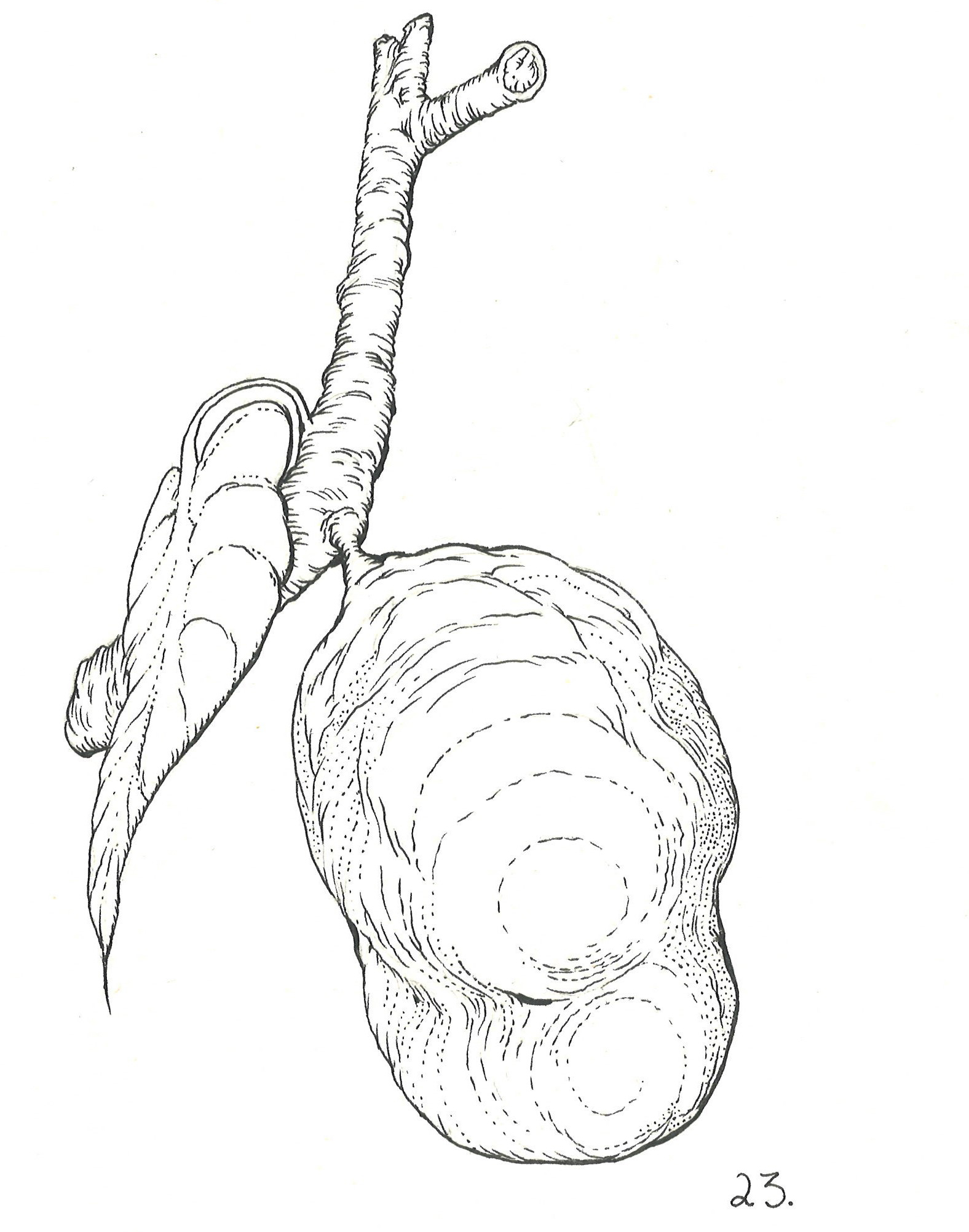

But from the gaping voids in the puzzles of time, a third claimant was discovered by the anthropologist Margaret Mead, in the shape of a bone. A femur – the longest bone in the human body, bridging hip and knee, was broken 15,000 years ago.

This broken bone in the paleolithic age, without recourse to modern medicine, would take six weeks to heal. In this time, you cannot run from danger, you cannot drink or hunt for food. Wounded in this state, you are but meat for your predators. Yet this particular fracture had healed.

This bone is evidence that the fallen had found someone who bound their wound, bandaged them, carried them to safety and tended to them through their recovery. The ancient femur reminds us that the origins of our civilization belong not in the push or the fall, but in our ability to rise again.