A Savage Detective of Photographic Truth: In Conversation with Shan Bhattacharya

A Savage Detective of Photographic Truth: In Conversation with Shan Bhattacharya

MALAVIKA MADGULKAR

24 June 2021

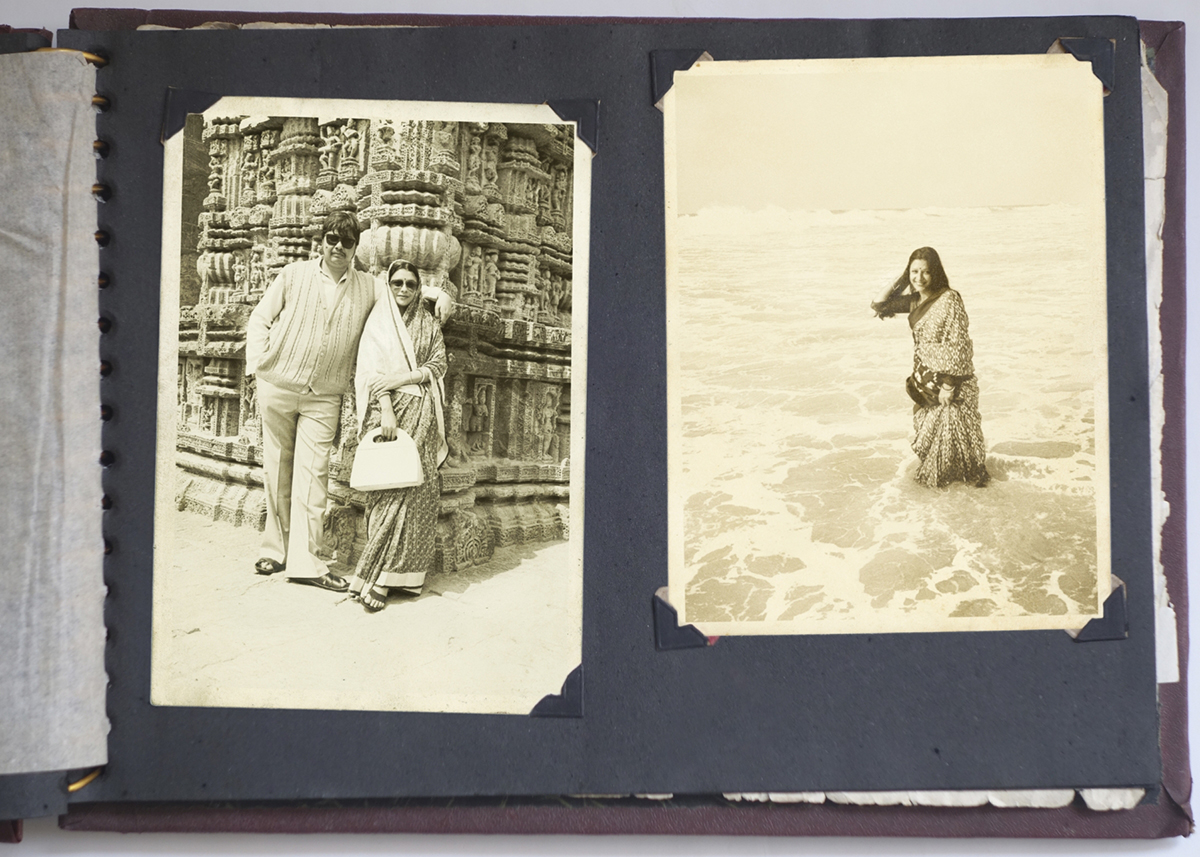

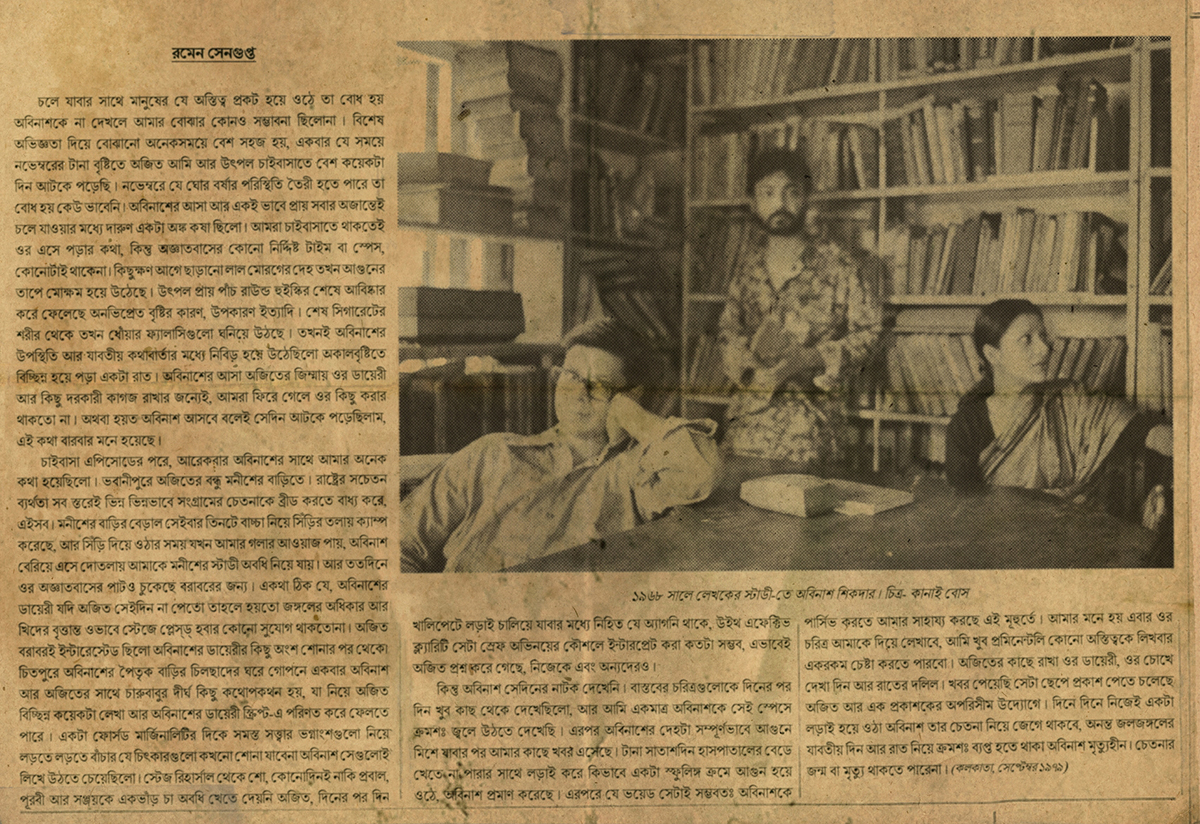

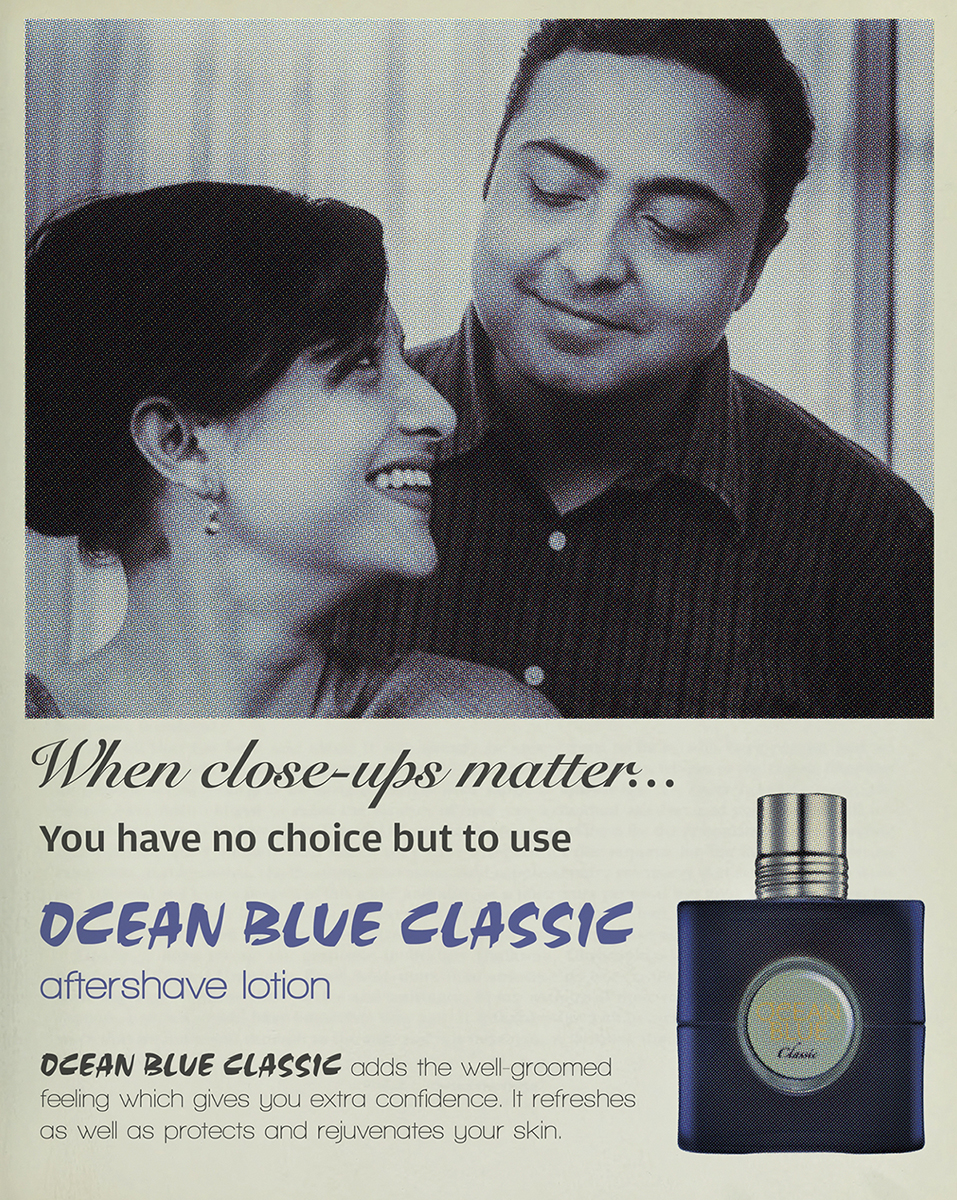

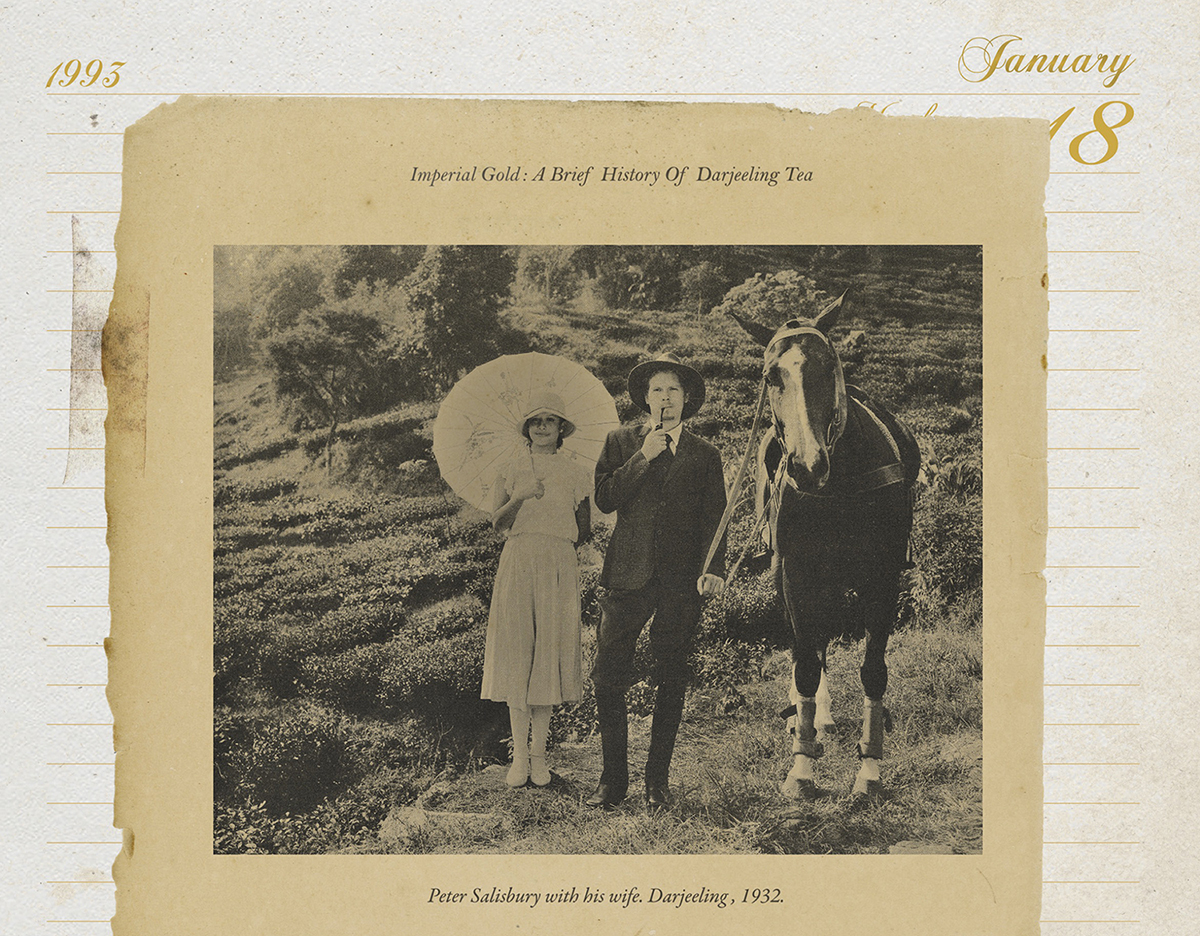

Shan Bhattacharya, the first grantee of the Umrao Singh Sher-Gil Grant for Photography, constructed his project in the form of a novella titled Portal: The Curious Case of Achintya Bose, a fictional story presented as the reproduction of a diary belonging to the owner of a small photography studio in Kolkata. Bhattacharya’s protagonist, Achintya Bose has the eerie experience of encountering the same woman, at the same age, albeit with different identities and names, in several different photographs that span a century. Portal presents Bose’s fervent documentation in his quest to make sense of a strange chain of events that leads to an even stranger hypothesis – the existence of an immortal woman who never grows old.

The novella is replete with studio photographs, newspaper clippings, letters, print advertisements presented as ‘evidence’ collected by Bose. Bhattacharya produced these images using historically accurate photographic techniques, allowing the reader to navigate through the history of local photography and urban life in the early years of India’s economic liberalization. Portal forms a unique mode of inquiry into the relationship photography shares with identity, about what it means to be photographed and whether such a thing as an objective gaze really exists. SSAF’s Malavika Madgulkar speaks to Shan Bhattacharya about the project’s conceptual development and its process, and also about what lies ahead.

MM: In your artist statement for the Umrao Singh Sher-Gil Grant, you mention that Portal was inspired by detective fiction. Could you tell us a bit about your relationship with the cultural form of the detective novel? Why did you choose to present your photographic work as a narrative in that tradition?

SB: The idea behind the work was to explore various ways of looking in different forms and usages of photographs in a vernacular historical context. Not just photographs, but also contemporary design, linguistics and other text-based items. Such work would naturally culminate into some kind of an archive. I chose a fictional narrative to serve as a container for this archive mostly because a fictional work isn’t required to be particularly exhaustive. Also, when placed within narrative fiction, the photographs themselves serve as the object of interest, rather than a storytelling tool. I used some tropes of a detective novel only because I wanted this narrative to present a puzzle. But in retrospect, it could have been any genre.

Shan taking an exposure using a Graflex top-handle Speed Graphic. First manufactured in 1912, Speed Graphic was the most ubiquitous press camera in the first half of the twentieth century. Photo by Abhra Aich.

MM: When producing the images for Portal, you were careful to use the exact techniques and cameras that would have been used at the point in history where the image is set. Why was it important to remain faithful to the authentic photographic practices of the given period, despite the fact that Portal is to be viewed outside the gallery space, only as a printed novella?

SB: Various visual aesthetics that become dominant in different eras in the history of photography often arise directly from the limitations of existing technology. In terms of cameras from different eras, apart from gross differences like film format or manufactural uniqueness, in many cases the differences are subtle, like perspective or depth. I am sure that if I had attempted to emulate all of that by putting carefully selected digital filters over images taken in a single digital camera, it would have been a tougher job for me, since I wouldn’t know what to refer to. Also, the book is a collection of photographs taken by different photographers. Using different equipment made it easier for me to come out of a technical comfort zone and step on different photographers’ shoes each time, working with different sets of limitations and looking from previously unfamiliar perspectives. I have also come to find that using equipment from the past somewhat helps the subjects’ expressions appear more authentic since the interaction goes both ways.

MM: It is a fascinating idea to think of photography equipment in this way as a tool for a two-way interaction. Could the title of your book, Portal, be considered an allusion to the camera or the process of photography itself?

SB: Thanks, that’s a nice way to look at it. There’s also this performative aspect of the photographic process and being photographed. It’s not just looking at various timeframes in the past through a bunch of old photos, but making a passage to experience it to some extent.

MM: The photographic archive is a highly political space – raising questions about representation, exclusion, access and collective memory. What, for you, are the politics of building a fictional archive like Portal? Are elements of fiction implicit in any archive?

SB: In Portal, Achintya Bose’s journal presents the collection that he had built, rather than his archive, only relevant portions of which are included later. I’d like to slightly differ from your analysis that the photographic archive itself is highly political. I think it is the responsibility of the one who’s accessing the archive to draw political implications from it, which could be several, often contradictory depending on the person. Different politically motivated collections can arise out of a single archive, because no photographic archive is truly complete, and no photograph truly depicts facts.

MM: Achintya Bose could be called an unreliable narrator. Despite all the photographic ‘evidence’ included in the novella, we remain unconvinced of the existence of an ‘immortal woman’. As such, Portal questions the idea of photography as an objective medium. How do you understand the relationship between photography and ‘objectivity’ or ‘truth’?

SB: As far as I understand it, the relationship between photography and so-called ‘objective truth’ got so much popularity in public discourse only after documentary photography associated with journalism became a dominant cultural form in the global political climate of the first half of twentieth century. Otherwise, from its inception photography has always been a tool of self-expression, like any other medium of communication. One can choose to narrate truth through it, or not.

© Shan Bhattacharya, ‘Portal’/Umrao Singh Sher-Gil Grant for Photography [2016], SSAF.

MM: Perhaps I’m thinking of Portal as provoking the link between photography and truth because it uses photography as an ‘evidential’ tool within a fictional narrative that presents itself as real. There is something about the medium of photography that speaks to the idea of a ‘hoax’ or a ‘trick’, would you agree?

SB: But of course. Even in a strictly legal scenario a photograph is assumed to contain facts, until proven otherwise. That’s how we as viewers are somewhat conditioned to treat a photograph as an evidential tool. Photographs lie, but more often than not they resemble the truth very closely in many aspects. Perhaps that’s why in the social media era so much of political propaganda tend to abuse this conditioning.

MM: How has our relationship to being photographed changed since the early ‘90s where the novella is set?

SB: Most definitely there has been a major shift in attitude. A huge majority of the urban/ semi-urban population is almost always being photographed, by themselves or by others, not only in public space but also in private. And we are not always fully aware of it. But subconsciously we accept it. I’d say the ‘90s were the last set of years for the regular everyman practicing traditional ways of being photographed. The post-9/11 political climate, subsequent technological innovations and the so-called ‘surveillance era’ have brought a massive shift to the general attitude towards being observed through a camera lens and recording. We only notice it when the device becomes too intrusive, and then our reactions often tend to be solely performative, in both rejection and participation.

MM: It is interesting you mention surveillance capitalism here. Your project questions the link between identity and faces and hints at the shortcomings of the process of facial recognition. Were you thinking about these questions in the context of photography today as you were exploring the history of this medium?

SB: To me ‘photography today’ is a bottomless pit. It’s nearly impossible to put a boundary on what constitutes photography as a practice. I wasn’t thinking of the impact of face recognition particularly in the context of modern photographic practice, but in general as another aspect of our social conditioning. It reminds me of this friend of mine, a social media influencer often practicing self-portraiture, who suddenly couldn’t unlock her face recognition-enabled smartphone after a radical haircut and styling.

© Shan Bhattacharya, ‘Portal’/Umrao Singh Sher-Gil Grant for Photography [2016], SSAF.

MM: At the end of the novella you include a scientific treatise by (presumably) a fictional scientist, explaining why Bose might recognize the same woman in photographs taken over a century. Why did you make the decision to end this mysterious, somewhat supernatural story on a note of scientific rationalism?

SB: Conjuring up an ‘expert’ third person to validate an unreliable narrator’s account is not an uncommon storytelling device. Traditionally it has been used in many fiction pieces that use this structure of retelling someone else’s story. I used this to provide a perspective on the scientific basis behind identifying faces from photographs and hoped the reader might want to go back to look at some photographs in the book (especially the ones where the central character’s face is partly obstructed or shown from another angle) with this knowledge.

MM: Could you tell us a bit about the projects you are working on currently? How do you imagine the experience of working on Portal to influence your practice in the future?

SB: Working on Portal helped me learn to expand my ideas to a wider scale, both conceptually and in terms of medium. Before this, my practice was mostly limited to photographing and trying to collectivize what I photographed. Apart from few commissioned works, I always start working on 2–3 project ideas at a time and after a while I concentrate on the one that picks up more pace than others and shelve the rest. In 2019, I thought I had one such idea and started concentrating on it. But it required me to travel around extensively, so I had no choice but to shelve it after March ’20. I am working on resuming it in 2021 besides getting back to the shelved others, trying to modify them and find out which one suits best at a time like this, but the future is uncertain.

© Shan Bhattacharya, ‘Portal’/Umrao Singh Sher-Gil Grant for Photography [2016], SSAF.

All images have been reproduced with permission of the author. Portal: The Curious Case of Achintya Bose is published by SSAF–Tulika Books. To order copies online, visit https://tulikabooks.in/catalog/product/view/id/21830