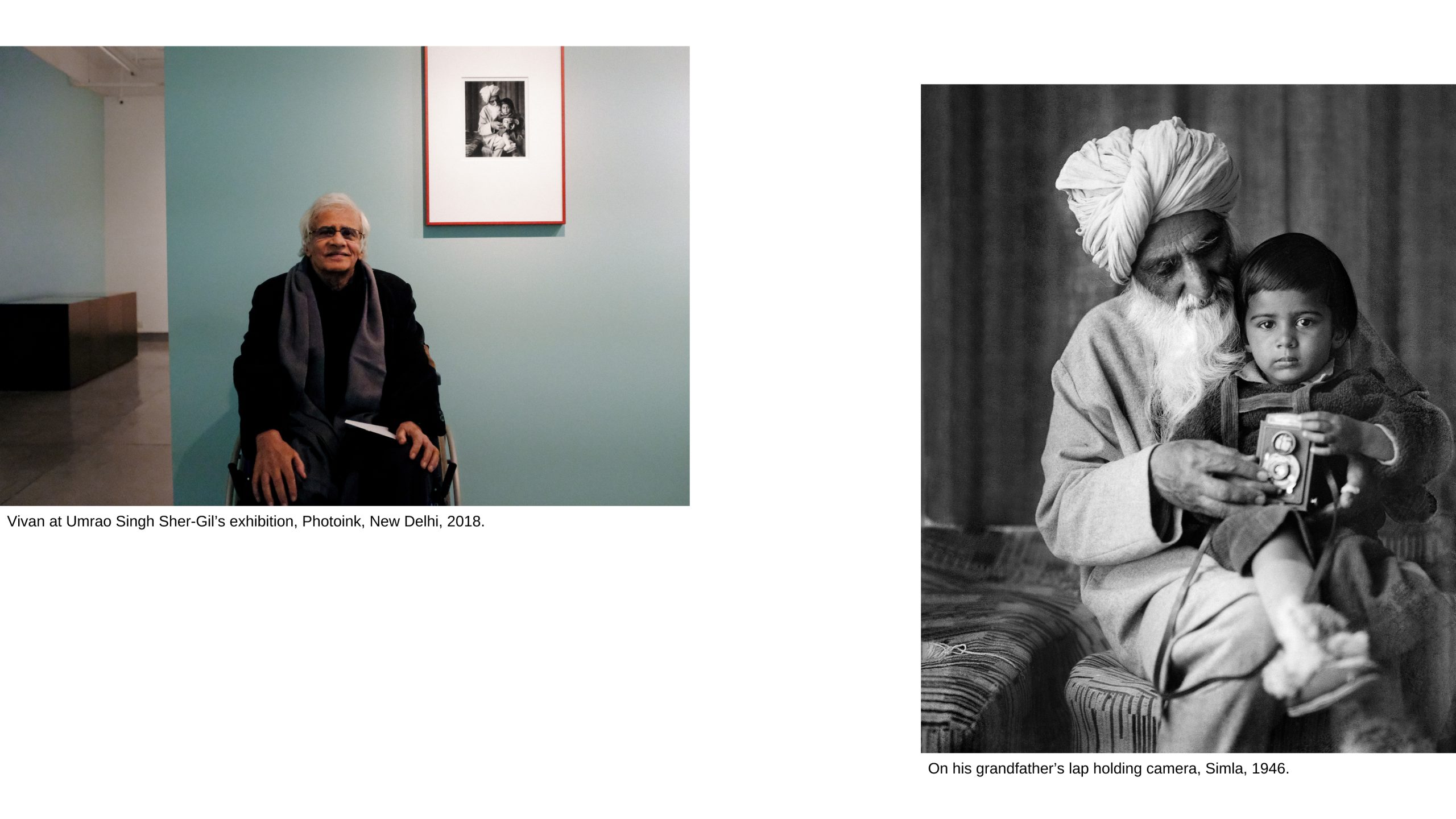

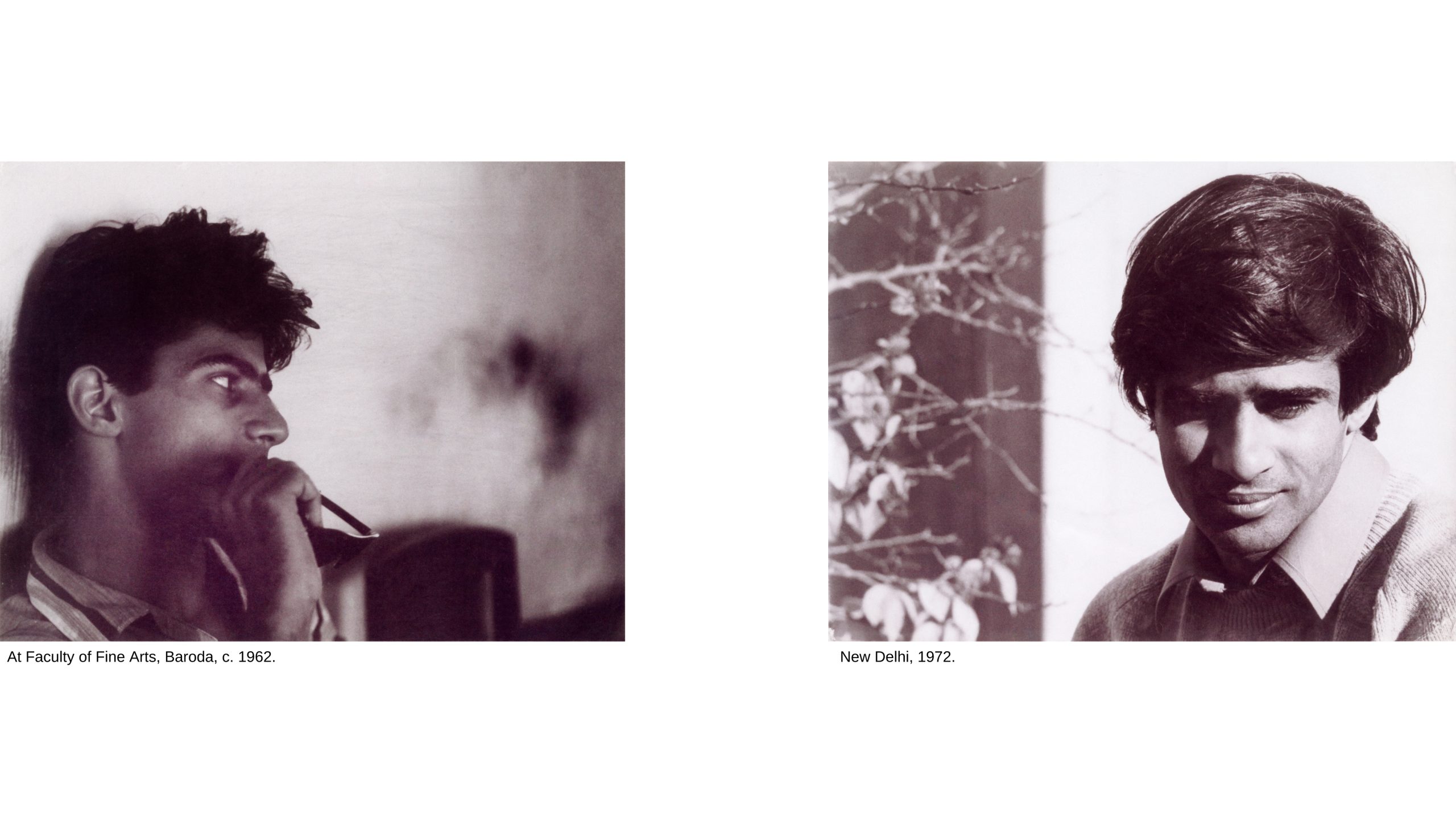

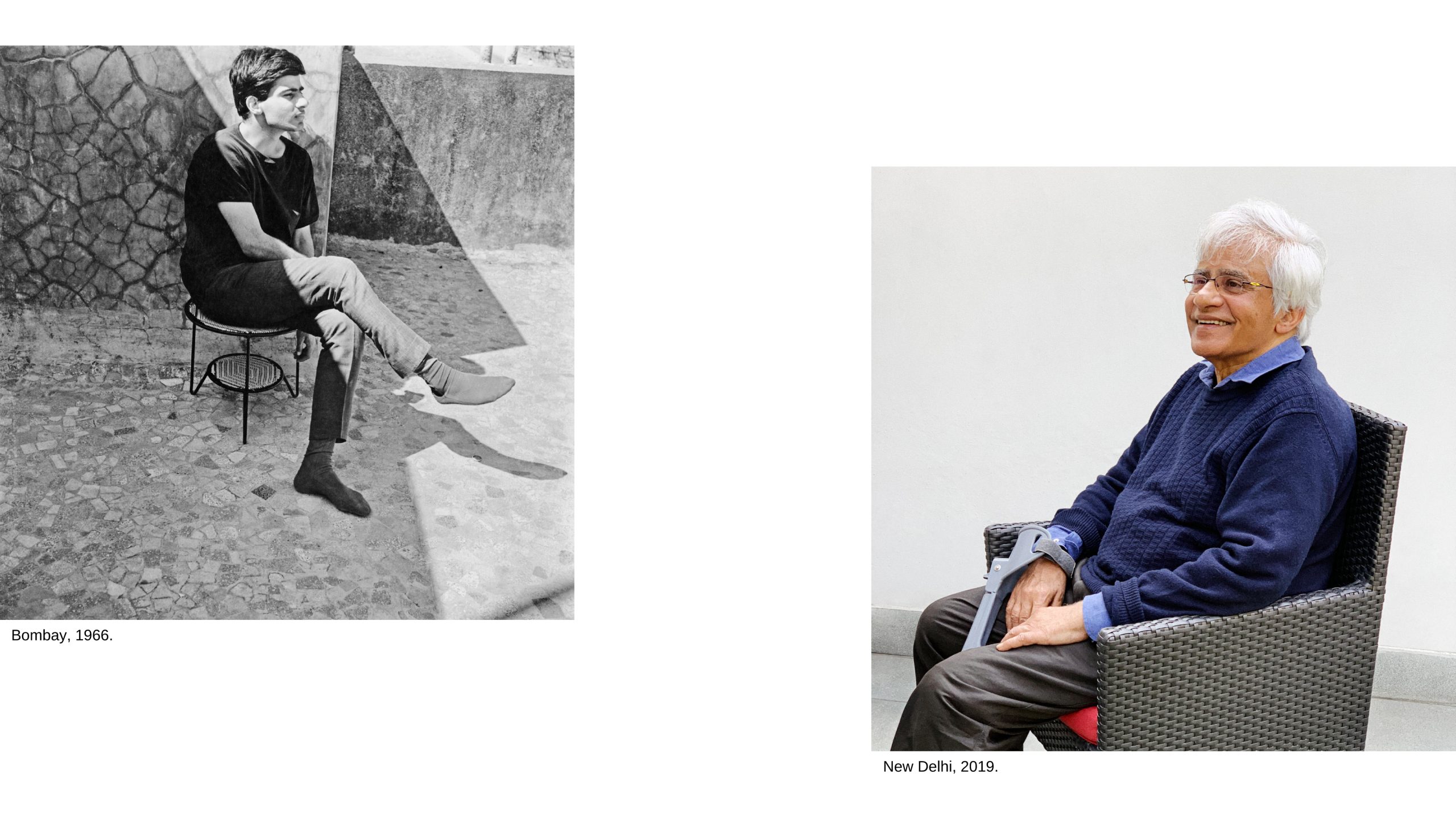

Vivan Sundaram was born in 1943, in Simla, Himachal Pradesh. He studied painting at the Faculty of Fine Arts, M.S. University of Baroda (1961–65) and at the Slade School of Art, London (1966–68) where he also studied History of Cinema. Active in the students’ movement of May 1968, he helped set up a commune in London where he lived till 1970. On his return to India in 1971, he worked with artists’ and students’ groups to organize events and protests, especially during the Emergency years.

In 1981, Sundaram participated in the seminal group exhibition, ‘Place for People’. From 1990, he made installations that include sculpture, photographs and video: Memorial (1993, 2001, 2014), an elaborate work made in response to communal violence in Bombay after the demolition of the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya in December 1992; a monumental site-specific installation at the Victoria Memorial, Calcutta, now referred to as History Project (1998); continuing work on his family, which includes the installation, The Sher-Gil Archive (1995), and a set of digital photomontages, Re-take of ‘Amrita’ (2001–02), based on photographs taken by Umrao Singh Sher-Gil. A series of exhibitions using found objects included Trash (2008), an installed urbanscape of garbage, digital photomontages and three videos: Tracking (2003–04), The Brief Ascension of Marian Hussain (2005) and Turning (2008). Garbage and found materials were used to make garments, and the work crossed over into fashion and performance in GAGAWAKA: Making Strange (2011) and Post Mortem (2013–14). In 2012, Black Gold, an installation of potsherds from the excavation of Pattanam/Muziris in Kerala, was made into a three-channel video. A project on the artist Ramkinkar Baij, 409 Ramkinkars, was co-authored with theatre directors Anuradha Kapur and Santanu Bose in 2015. In 2017, a public art project on the uprising of the Royal Indian Navy and Bombay’s working class, titled Meanings of Failed Action: Insurrection 1946, was co-authored with cultural theorist Ashish Rajadhyaksha and sound artist David Chapman.

A 50-year retrospective exhibition, ‘Step inside and you are no longer a stranger’, invited by the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi, showed from February to June 2018. A solo survey exhibition titled ‘Disjunctures’, invited by Okwui Enwezor and curated by Deepak Ananth, showed at Haus der Kunst, Munich, from June 2018 to January 2019.

Most recently, Vivan Sundaram was one of 30 artists specially commissioned to make new work to mark the Sharjah Biennial’s 30th anniversary edition. The Sharjah Biennial 15: Thinking Historically in the Present (February to June 2023), conceived by the late Okwui Enwezor and curated by Hoor Al Qasimi, included Sundaram’s photography-based project, Six Stations of a Life Pursued (2022), signifying a journey with periodic halts that release pain, regain trust, behold beauty, recall horror, and discard memory. His Memorial, now in the collection of London’s Tate Modern, was posthumously displayed in the museum’s enormous South Tank from April to September 2023.

Sundaram exhibited in the Biennales of Havana, Johannesburg, Gwangju, Taipei, Sharjah, Shanghai, Sydney, Seville, Berlin, and in the Asia-Pacific Triennial, Brisbane. He had solo shows in many cities of India, as well as in London, Paris, Toronto, Montreal, Vancouver, Amsterdam, Budapest, Copenhagen, New York, Chicago, Dallas, and at the Fowler Museum, Los Angeles.

Vivan Sundaram was an artist-activist and used different strategies for artists’ collaboration. As founding member of the Kasauli Art Centre, he organized artists’ workshops and seminars at the Centre from 1976 to 1991. He contributed variously to the Journal of Arts & Ideas (1981–99) as a member of its editorial collective. As a founder trustee of the Safdar Hashmi Memorial Trust (SAHMAT) he initiated art projects and curated political, left-oriented exhibitions that were shown across the country and engaged with the public domain through innovative formats.

Sundaram is the editor of a definitive two-volume book on Amrita Sher-Gil, titled Amrita Sher-Gil: a self-portrait in letters & writings (2010). Books published on his art projects include Vivan Sundaram: History Project, a site-specific installation, Victoria Memorial, 1998 (2017) and Vivan Sundaram Is Not a Photographer: The Photographic Work of Vivan Sundaram by Ruth Rosengarten (2019).

Vivan Sundaram was founder and managing trustee, with his sister Navina Sundaram, of the Sher-Gil Sundaram Arts Foundation (SSAF), which was set up in 2016. It offers grants for creative projects, initiates curation, undertakes publications, and organizes lectures and symposia for furthering art discourse.

Vivan at Ivy Lodge, Kasauli, 2016. Photo by Neelam Man Singh Chowdhry.

The Stations of the Cross

Ashish Rajadhyaksha

Time, Vivan Sundaram boldly announced in 2018, ‘was on my side’. He was of course speaking of a far more memorable moment in time than the present one. Time indeed had appeared to have been on his side during the ‘year of the barricades’.

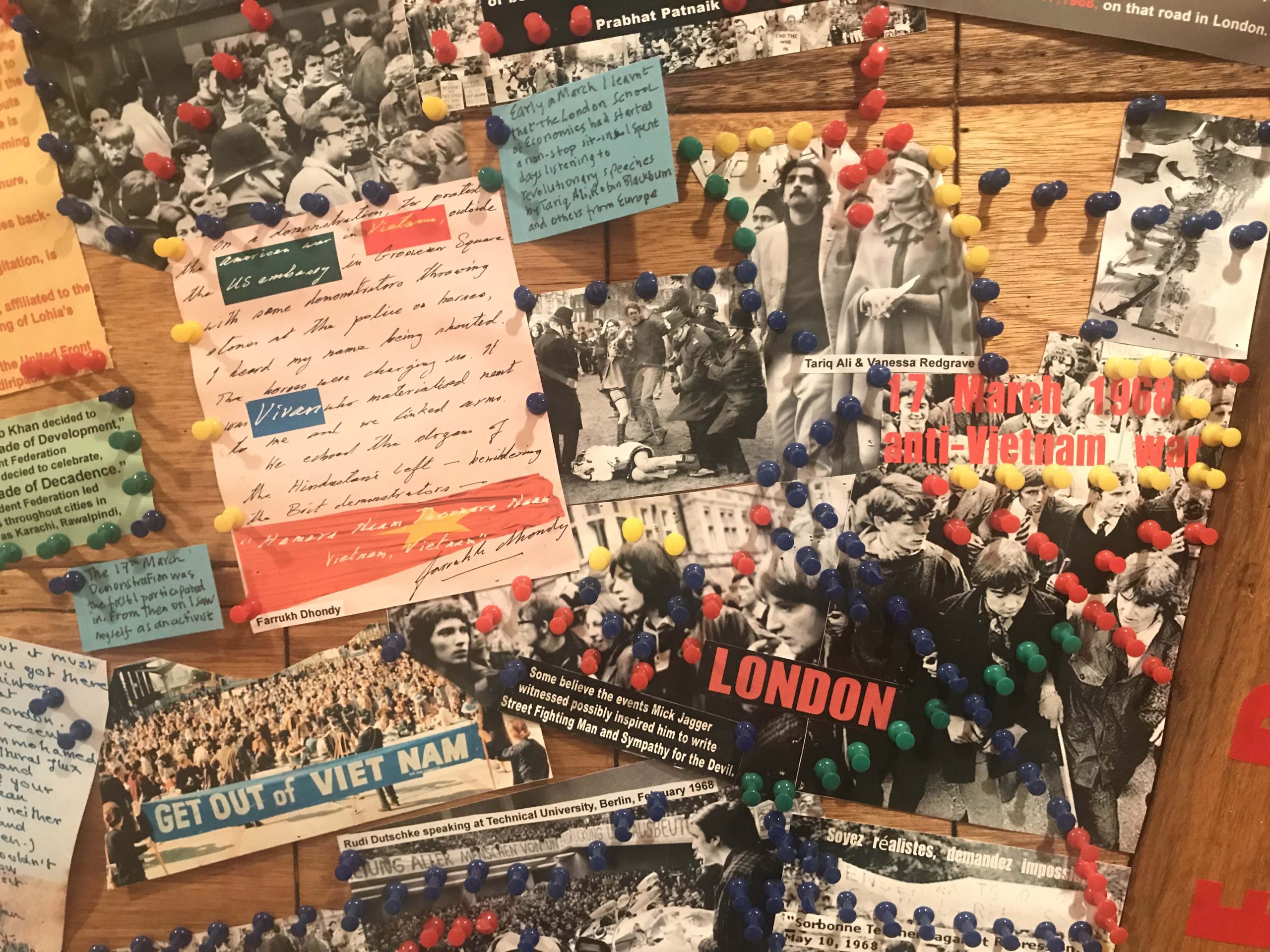

Vivan liked talking about this period, and he usually did it with bold strokes. He was a student in London between 1968 and 1970, and reminisced freely about the Slade School of Art, his life in the commune at 154 Barnsbury Road, London, and even his brief stint in Wandsworth jail. That March of 1968 he had been at the famous anti-War demonstration outside the American Consulate in London’s Grosvenor Square. Protests had taken place in Boston, Warsaw, Nanterre, Berlin and New York, and strikes by students and workers had spread across much of Western Europe, many protesting the Vietnam War.

And yet, as he presented it that day, the era proved rather more complicated than its more conventionally romanticised portraiture of halcyon youth. For even at that time – even as he went to concerts by Bob Dylan and the Rolling Stones and marched alongside Mick Jagger and Tariq Ali – the pulls of Indian art, and more generally non-Western art, had to also be addressed: pulls that necessarily took him to global considerations far removed from the immediacy of that particular frontline. History arrived as something to be recognized and retrieved from within the material he saw all around him. He recalled in that talk how he rediscovered his painting May 68 from an attic, and used it to inaugurate his major retrospective Step Inside and You Are No Longer a Stranger at the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art that was going on as he spoke in 2018. He now showed that painting alongside stone-pelting protesters in Paris and the scrawled graffiti ‘under the paving stones, the beach’ – or, he might have also said, under the rubble, history itself.

May ’68, 1968.

From Persian Miniatures to Stan Brakhage, 1968.

And then he went further. Alongside May 68 was Stan Brakhage’s extraordinary multimedia film Dog Star Man. Next to it was a detail from Kitaj’s Erie Shore. And finally, an unnamed Persian miniature. In short, possible materials of a collage of this time that needed excavation. Collage was a term Vivan carried like a badge, even as it became something of a time-machine collapsing different temporalities. A seminal work of that time, From Persian Miniatures to Stan Brakhage (1968) is a painting-within-a-painting, a beneath-the-surface world-within-a-world. Pop art had arrived, he said, in Baroda as far back as 1964 (in his own work together with that of the early Bhupen Khakhar), the very year Robert Rauschenberg had won the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale. Rauschenberg remained, alongside the painter R.B. Kitaj – his teacher at the Slade – the twin contrasting presences defining his work in this time; pop, diverse media, jostling with the demands of classic oil-on-canvas.

Collages of History

It was a strange assemblage. There were, speaking from even his own 2018 indications at least three, maybe more, directions to take as he found himself at a curious crossroads of history, at once personal and planetary. You could see, as he outlined the year of the barricades in 2018, that he was even then preparing subjectively for some kind of action.

Major arcs can now be drawn from the actions that indeed followed. For the time that was on his side would become, both in the talk and the 2018 retrospective, visible and interpretable as a gigantic template for projects that would be realized over the decades. One came from the ineluctable pressure of history itself. He was moving at once between monumentalism and minimalism: at one moment outward towards public art and at another inwards, into deeply disquieting inner spaces of depression and even death. In 1998 the gigantic installation at Kolkata’s Victoria Memorial, now known as the History Project, would be precisely located here and would, with Vivan’s typical audacity, further locate an Indian history of a hundred years or more into that tension.

Installation View of History Project, 1998 at Victoria Memorial Hall, Kolkata.

The once-youthful jostling of pop art, abstract expressionism and classical painting would, as the years went by, reveal both immediacy and the dangers of deeply personal-political moments. There was the Place for People exhibition that defined the painterly moment in 1981 – in many ways the best-known oil-on-canvas by several of Indian art’s major hall-of-famers: Bhupen Khakhar, Gulammohammed Sheikh, Sudhir Patwardhan, Nalini Malani – almost all turning their gaze inwards, to themselves, their private spaces, their families and loved ones. This deep personal would resurface in the entire series of photomontages beginning with Re-take of Amrita, working as always with its polar opposite, the Trash series. And then there was the spillover of that moment, into action – an activism that emerged from the art.

Bourgeois Family: Mirror Frieze, 2001. Re-take of Amrita series. [From left: Indira, Paris, 1930; Umrao Singh and Vivan, Simla, 1946; Marie Antoinette, Lahore, 1912; Small Earring, 1893, Georg Hendrik Breitner; Amrita, Simla, 1937; Amrita, Budapest, 1938, photo, Victor Egan.]

The ‘subject’ of politics

It is commonplace to describe Vivan, as it is most of the above-mentioned names, as ‘political’. It is also commonplace to go further and bestow upon him the compelling image of forever-youthful radicalism, for he attracts such an idealized image to himself. But that would be a disservice, not because it is untrue but because it is limiting. We need to get at the problem, the knots that tied the many directions that pulled him, and to do that we need to enter what we might call the subjective condition of politics as we experience it in India. While the deeply fraught histories of conflict that have beset political art worldwide have been extensively chronicled, nowhere more so than in India, we have yet to take seriously just what theory of politics made works of art political. When we do, it takes us to the risks, indeed – as Partha Chatterjee said of that most quintessential of political artists, Sadat Hasan Manto – the dangerousness of that condition. Such a danger is presented mainly in the way which an artist offers their subjectivity as a space upon which to play out very large historical battles. It is an endeavor that is only partially captured by its most visible manifestation, namely the practical legal, political and human-rights dangers inherent to confronting authority.

What we need to do, then, as we recognize Vivan’s life and work, is to understand how his artistic persona led to a major radicalization of the concept artist. It did so in the way this persona effectively evacuated its egotistical content into something of a void, an absence, and thence an invitation to enter and be a stranger no longer. Such a void became, to borrow from Vivan’s key work, the Long Night series, a zone, a site for struggles around a new form of political subjectivity. It was one that he sometimes occupied alone, but more often collectively assembled: shared with other artists, collaborators and eventually audiences – as for instance in the remarkable installation-performance he called 409 Ramkinkars and staged with several actors, theatre director Anuradha Kapur, and many other artists.

This question, who is the artist-citizen, is especially relevant at a time when political theory in India appears to itself be in transformation: one to which Vivan’s work bears great relevance. It is a political world that is more fundamental than traditional ideological disputes, more likely a subjective frontline – immensely relevant to diverse political struggles going on today in various parts of the world – an immersive relation of bodily self into something far more complexly engaged with the political moment than the classically defined idea of painter-citizen working at a creative remove from the rubble of the everyday. This we saw in early and youthful mode in 1968 and this is what we have seen again and again as the decades have gone by.

Such a figure was always there in Vivan, but it emerged in perhaps his most ‘political’ work of all, the 1993 installation Memorial in which he took a news photograph of a dead man, killed and abandoned on the streets, and gave him a burial with full state honours. He did so with a repetitive action, of banging in thousands of tiny nails, of performing the same gesture again and again and again, of performing repentance in the way the state could no longer do. As the capacity to embody – I mean this literally – such a split becomes a qualification for personhood, we begin to see how even the dead, killed as collateral damage, become corporeal, posthumously demanding the state recognition of their own right, if nothing else, to die.

Installation view of Memorial, 1993, 2014 at Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi during Vivan’s retrospective ‘Step Inside and You Are No Longer a Stranger’ (February 9-June 30, 2018).

This author was a participant-eyewitness to what was perhaps Vivan’s last work of explicitly ‘political’ monumentalism: the 2017 Meanings of Failed Action, a massive installation and sound work that also became the centerpiece of his 2018 retrospective. It was about the 1946 naval uprising in Bombay, and mounted as a giant ship or ‘container’, inside which the sound played to a lighting design. The original idea was in a way wider: to do a project focused on the geographical – and we saw, also historical – proximity of the naval dockyard to the working class neighbourhoods of Parel and Lalbaug. It did not happen as planned. As it went on, and deepened, there was a shift in the focus as more substantially historical questions – the ‘meanings of failed action’, as the title now shows – grew in significance.

Several of the original links with the mills and docks remains strong: indeed, it provided the key rationale for the work’s first install in Mumbai’s Coomaraswamy Hall, and for the events that took place inside the hull. Its producers now included the long-dead mutineers, whose own archives – their letters, pleas for consideration from the newly independent Indian state, the many historians and activists whose voices featured in the sound work – were now extended into conversations with historians – from naval historians to city historians to historians of the Second World War – as well as artists and architects from the city, all of whom had a stake in this history, and wanted to share in that moment of time.

It is almost as though the finale, the work currently on display at Sharjah, Six Stations of a Life Pursued (2022) constitutes the culmination of a political project that he may have begun a long time ago. We’re literally speaking of the artist as bodily subject here, as the lacerations on Vivan’s back (following major medical procedures) turn into stigmata. But then that body merges, as it always does in his work, with other bodies – a wounded body with, as the accompanying text to the work says, ‘proof of torture’ extending into ‘mourning bodies in the realm of shadows; body as miasma floating on a city lake; familial bodies in the mode of a charade; and, at the end, the iconic body that dares to represent the historical present—of a place, a nation, a territory, a people.

It really was as though the image of the red flag gently passing over the barricades of the 60s, with which Vivan ended his 2018 talk, had also wafted over this at times gentle, at others horrific landscape. Time was then, and who knows may still be, on his side.

Time is on my side: Vivan London 1968 is adapted from an illustrated talk Vivan Sundaram gave on March 22, 2018, during his retrospective ‘Step Inside and You Are No Longer a Stranger’ (February 9-June 30, 2018) at the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art. The assemblage draws upon a keynote file made by Vivan and a video recording of the talk, and was edited by Babu Eshwar Prasad for Vivan’s memorial meeting in Delhi on 17 April 2023. Grateful acknowledgment: Kiran Nadar Museum of Art

*The article was first published in Frontline, Volume 40 No. 08, May 5 2023.

Many Voices: Remembering Vivan

- National Herald

Goodbye, fellow navigator: Ranjit Hoskote pays tribute to Vivan Sundaram (28 May 1943 – 29 March 2023)

Ranjit Hoskote

- THE AIDEM

Teesta Remembers Vivan

Teesta Setalvad

- The Wire

Vivan Sundaram (1943–2023): The Boy in the Mirror

Roobina Karode

- The Indian Express

Vivan Sundaram: An artist who truly lived his ideology and responded to crises of the times

Vandana Kalra

- Critical Collective

Vivan Sundaram (1943-2023)

Gayatri Sinha

- The Wire

The Vivan I Knew, Lively, Energetic and Pathbreaking in His Art and Life

S. Kalidas

- The Indian Express

Sudhir Patwardhan writes: Vivan Sundaram was an institution builder, and was instrumental in opening up opportunities for younger artists

Sudhir Patwardhan

- STIR World

Remembering artist, activist, archivist Vivan Sundaram (1943–2023)

Meera Menezes

- Telegraph India

Artist of Turbulence

Ruchir Joshi

- Mint

‘My art warrior’: a gallerist remembers Vivan Sundaram

Shireen Gandhy

- The New York Times

Vivan Sundaram, 79, Dies; a Pivotal, and Political, Figure in Indian Art

Holland Cotter

- Artforum

VIVAN SUNDARAM (1943–2023)

Rattanamol Singh Johal

- Frontline, The Hindu

Vivan Sundaram (1943-2023): Rebel, writer, thinker, artist

Ashish Rajadhyaksha

- TAKE on Art

Remembering Vivan Sundaram: 1943-2023

Emilia Terracciano

- Scroll.in

Art and revolution: Vivan Sundaram, an artist whose work captured the turmoil of contemporary times

Sujata Prasad

- The Art Newspaper

Remembering Vivan Sundaram, one of India’s leading artists and a champion of the country’s post-independence visual culture

Natasha Ginwala